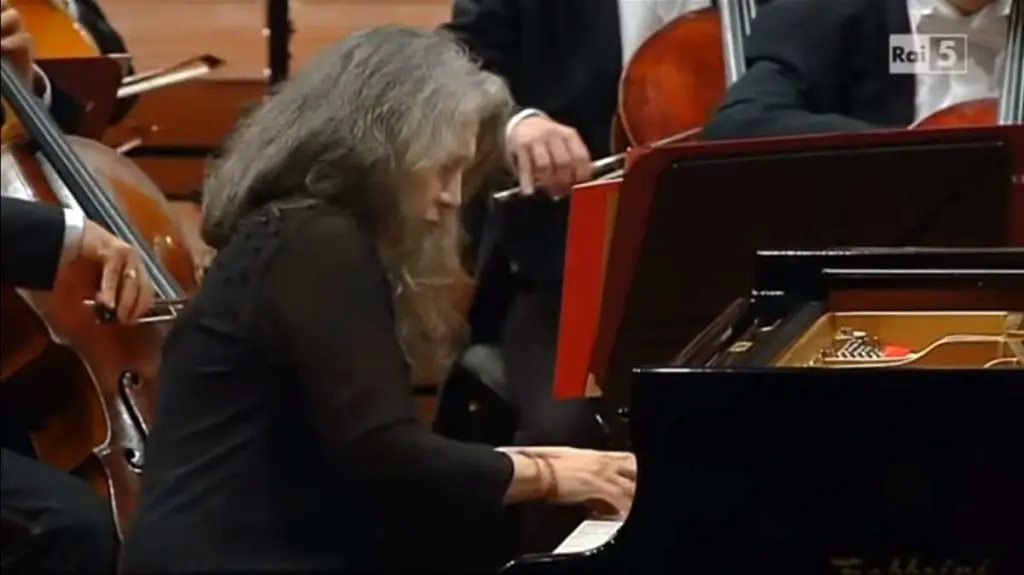

Widely considered one of the greatest pianists of all time, Russian-American classical pianist Vladimir Horowitz plays Robert Schumann’s Kinderszenen (original spelling Kinderscenen, “Scenes from Childhood”), Opus 15, a set of thirteen pieces of music for piano written during the spring of 1838. Recorded in Vienna in 1987.

Program

- 00:38 Scene No.1 | Von fremden Ländern und Menschen (Of Foreign Lands and Peoples)

- 02:09 Scene No.2 | Kuriose Geschichte (A Curious Story)

- 03:15 Scene No.3 | Hasche-Mann (Blind Man’s Bluff)

- 03:48 Scene No.4 | Bittendes Kind (Pleading Child)

- 04:38 Scene No.5 | Glückes genug (Happy Enough)

- 05:17 Scene No.6 | Wichtige Begebenheit (An Important Event)

- 06:09 Scene No.7 | Träumerei (Dreaming)

- 08:43 Scene No.8 | Am Kamin (At the Fireside)

- 10:02 Scene No.9 | Ritter vom Steckenpferd (Knight of the Hobbyhorse)

- 10:43 Scene No.10 | Fast zu ernst (Almost Too Serious)

- 12:12 Scene No.11 | Fürchtenmachen (Frightening)

- 13:52 Scene No.12 | Kind im Einschlummern (Child Falling Asleep)

- 15:31 Scene No.13 | Der Dichter spricht (The Poet Speaks)

Vladimir Horowitz’s technique, use of tone color, and the excitement of his playing were considered legendary. He is widely considered one of the greatest pianists of all time.

Robert Schumann’s Kinderszenen Op. 15 “Scenes from Childhood”

In this work, Schumann provides us with his adult reminiscences of childhood. Schumann had originally written 30 movements for this work but chose 13 for the final version.

When Robert Schumann (8 June 1810 – 29 July 1856) wrote Kinderszenen, he was deeply in love with Clara Wieck (13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896), soon to become his wife over the objections of her overbearing father. The composer worked at a feverish pace, composing these pieces in just several days.

Actually, he wrote about thirty small pieces but trimmed them to the thirteen that comprise the set. The 13 pieces showcase their creator’s musical imagination at the peak of its poetic clarity. As a result, the Kinderszenen have long been staples of the repertoire as utterly charming yet substantial miniatures, the sort of compact keyboard essays in which Schumann’s genius found full expression.

In March of that year, Schumann wrote to Clara, “I have been waiting for your letter and have in the meantime filled several books with pieces… You once said to me that I often seemed like a child, and I suddenly got inspired and knocked off around 30 quaint little pieces… I selected several and titled them Kinderszenen. You will enjoy them, though you will need to forget that you are a virtuoso when you play them.”

The Kinderszenen “Scenes from Childhood” are a touching tribute to the eternal, universal memories and feelings of childhood from a nostalgic adult perspective. They are fairly simple in terms of execution, and their subject matter deals with the world of children. From spirited games to sleeping and dreaming, Kinderszenen captures the joys and sorrows of childhood in a series of musical snapshots. Schumann described the titles as “nothing more than delicate hints for execution and interpretation”.

Schumann claimed that the picturesque titles attached to the pieces were added as an afterthought in order to provide subtle suggestions to the player, a model Debussy followed decades later in his Preludes. Scene No. 1, “Von fremden Ländern und Menschen” (Of Foreign Lands and People), opens with a lovely melody whose basic motivic substance, by appearing in several vague guises throughout many of the other pieces, serves as a general unifying element.

The seventh Scene, “Träumerei” (Reverie), is easily the most famous piece in the set; its charming melody and quieting power have recommended it to generations of concert pianists who wish to calm audiences after a long series of rousing encores.

The Kinderszenen contains many delicate musical touches; Scene No. 4, “Bittendes Kind” (Pleading Child), for example, is harmonically resolved only when an unseen force (a parent?) gives in and grants the child’s wish at the beginning of No. 5, “Glückes genug” (Quite Happy).

In the final piece, “Der Dichter spricht” (The Poet Speaks), Schumann removes himself just a bit from the indulgent reverie to formulate a narrator’s omniscient view of the child. Quietly, gently, the many moods and feelings that Schumann touched upon over the course of this remarkable 20-minute work are lovingly recalled, and the composition concludes, contentedly, in the same key of G major in which it began.

The seventh item here, “Träumerei” (Dreaming), is the most popular in the set. It is a depiction of childhood innocence, vulnerability, and gentleness. Many pianists have interpreted this piece in a sentimental, almost saccharine way, while others (Horowitz notably) have insisted on a more objective approach.

The main theme is sweetly innocent and sentimental, clearly representing the adult Schumann’s fond view of aspects of his own childhood. The melody is unforgettable, the harmonies simple, but distinctive, and the overall mood dreamy and soothing. Of the many themes associated with children – that in Brahms’ Lullaby, and several in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf – the “Träumerei” melody is among the most memorable. The whole piece lasts under three minutes but is the longest in the Kinderszenen set.

Related: Schumann – Arabeske [Emil Gilels]

Sources

- Kinderszenen on Wikipedia

- Kinderszenen, Op.15 (Schumann, Robert) on the IMSLP website

- “Kinderszenen”, op. 15 on the Villa Musica chamber music guide website