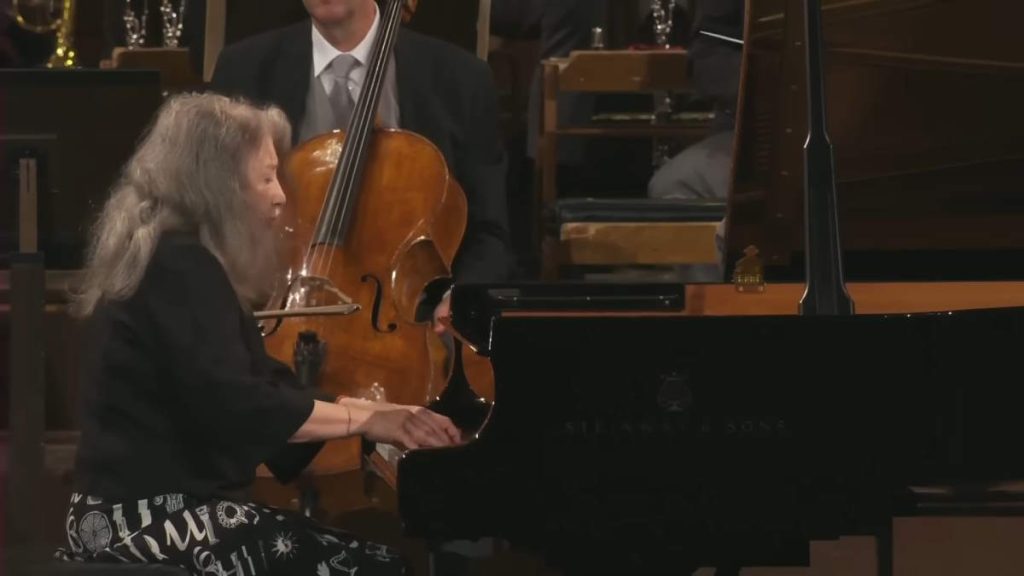

Accompanied by the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, the great Argentine pianist Martha Argerich performs Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, a romantic concerto completed in 1845. Conductor: Antonio Pappano. Recorded live in Rome on November 19, 2012.

Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto

Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, stands as one of the most cherished works in the Romantic piano concerto repertoire, embodying the depth of emotion and the innovative spirit that characterizes Schumann’s music. Composed in 1845, this concerto was Schumann’s only completed piano concerto and marked a significant contribution to the Romantic era’s musical landscape. It was premiered in Dresden in 1845 with his wife, Clara Schumann, a renowned pianist, performing the solo part, further cementing the concerto’s place in the canon of Romantic music.

This 1848 portrait by Franz von Lenbach (13 December 1836 – 6 May 1904) was a German painter of the Realist style.

Photo: Wikipedia

The concerto is noted for its seamless integration of the solo piano and orchestra, a departure from the more confrontational style of earlier concerti where the soloist and orchestra often played in opposition. Schumann instead opts for a collaborative approach, with the piano and orchestra engaging in a continuous dialogue throughout the work. This integration reflects Schumann’s desire to create a more symphonic type of concerto, where the emphasis is on musical expression and unity rather than virtuosic display.

Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor is also remarkable for its lyrical qualities and emotional range. The work traverses a wide spectrum of moods and colors, from passionate and dramatic to tender and introspective. Schumann’s genius in melodic invention and harmonic innovation is evident throughout the concerto, as he crafts themes of profound beauty and complexity.

The concerto’s structure and thematic development reflect Schumann’s interest in cyclic form, with motifs and themes recurring and evolving across the movements. This cyclical approach contributes to the concerto’s cohesive feel, binding the work together in a way that was quite innovative at the time.

Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto was premiered in Leipzig on January 1, 1846, with one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, Clara Schumann (13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896), the composer’s wife, playing the solo part. The orchestra was conducted by the work’s dedicatee, Ferdinand Hiller (24 October 1811 – 11 May 1885), the German composer, conductor, writer, and music director.

The concerto is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings, and solo piano.

Movements

1. Allegro affettuoso

The first movement of Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, is marked “Allegro affettuoso.” This opening movement beautifully encapsulates the Romantic spirit, blending passionate intensity with lyrical tenderness. From the very beginning, Schumann sets the stage for a deeply expressive dialogue between the solo piano and the orchestra, a hallmark of the entire concerto.

The movement starts with a powerful orchestral introduction, quickly giving way to the piano’s dramatic entrance. The solo piano part is both virtuosic and expressive, featuring sweeping arpeggios and robust chords that set the tone for the movement. The main theme introduced by the piano is rich in emotional depth, characterized by its affectionate and yearning quality.

Schumann’s innovative approach to the concerto form is evident in how he weaves together the solo and orchestral parts. Unlike the traditional concerto, where the orchestra often serves as a backdrop to the soloist’s display, Schumann creates a more integrated and conversational relationship between the piano and the orchestra. This results in a richly textured musical fabric, where themes are passed back and forth, developed, and transformed.

The development section explores a range of emotions and musical ideas, with Schumann demonstrating his mastery of harmonic color and thematic development. The piano and orchestra engage in an intricate exchange, building tension and complexity before leading to the recapitulation, where the main theme returns, now transformed and enriched by the journey.

The movement concludes with a coda that revisits the opening themes, culminating in a powerful and affirming conclusion. This coda not only brings closure to the movement but also showcases the soloist’s technical prowess and emotional expressivity.

2. Intermezzo: Andantino grazioso

The second movement of Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, is titled “Intermezzo: Andantino grazioso.” Following the passionate and expansive first movement, this Intermezzo offers a contrasting mood of delicate intimacy and lyrical grace. It serves as a bridge between the dramatic first movement and the vigorous finale, yet it holds its own unique charm and character within the concerto’s overall structure.

Characterized by its subtle beauty and understated elegance, the Intermezzo showcases Schumann’s skill in crafting music that speaks with a tender and personal voice. The movement begins quietly in the strings, setting a serene and somewhat introspective tone. The piano enters with a light, graceful theme that complements the strings, enhancing the movement’s intimate atmosphere.

The interplay between the solo piano and the orchestra in this movement is particularly noteworthy. Unlike the more dynamic and forceful dialogue in the first movement, here the interaction is gentle and conversational, with the piano and orchestra exchanging musical ideas in a manner that feels like a private conversation. This reflects Schumann’s Romantic ideal of music as a deeply personal and expressive medium.

The structure of the Intermezzo is relatively simple, focusing on the beauty of the melodic lines and the clarity of the harmonic language. However, within this simplicity lies a depth of emotion and craftsmanship. Schumann employs subtle variations in dynamics and articulation to create a piece that is both captivating and nuanced.

As the movement progresses, it maintains its lyrical and graceful character, with the piano weaving intricate melodies over the supportive harmonies of the orchestra. The movement concludes quietly, leaving a lingering sense of tranquility and introspection, effectively setting the stage for the energetic finale that follows.

3. Allegro vivace

The third movement of Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, marked “Allegro vivace,” serves as a vibrant and triumphant conclusion to the concerto. This finale is characterized by its energetic rhythm, brilliant piano passages, and a joyful mood that contrasts with the more introspective nature of the preceding Intermezzo.

From the outset, the movement bursts forth with a lively tempo and a sense of jubilant celebration. The piano introduces the main theme, a spirited melody that is both catchy and technically demanding. The theme is notable for its rhythmic drive and the way it propels the movement forward, showcasing the soloist’s virtuosity and expressive range.

Schumann’s orchestration in this finale is masterful, providing a colorful and dynamic backdrop that complements and interacts with the piano part. The orchestra and piano engage in a spirited dialogue, with the orchestral sections contributing their own thematic material and responding to the piano’s lead. This interplay enhances the overall sense of excitement and momentum throughout the movement.

One of the remarkable aspects of this finale is Schumann’s use of thematic integration. Motifs from the previous movements reappear, transformed and integrated into the fabric of the third movement, creating a sense of cohesion and unity within the concerto as a whole. This cyclical approach to thematic material was quite innovative at the time and adds depth to the structural and emotional impact of the finale.

The movement progresses through a series of virtuosic passages for the piano, including rapid scales, arpeggios, and challenging fingerwork, all of which demand a high level of technical skill from the performer. Despite these technical demands, the music never loses its inherent lyrical quality and emotional warmth, traits that are characteristic of Schumann’s compositional style.

As the movement approaches its conclusion, the energy and excitement build to a climax, culminating in a triumphant and joyful ending. The piano and orchestra come together in a final statement of the main theme, bringing the concerto to a close with a sense of exhilaration and accomplishment.

Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia

The Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia) is an Italian symphony orchestra based in Rome. Resident at the Auditorium Parco della Musica, the orchestra primarily performs its Rome concerts in the Auditorium’s Salla Santa Cecilia.

The orchestra was founded in 1908, as the first Italian orchestra to devote itself exclusively to symphonic repertoire. Bernardino Molinari was the orchestra’s first music director, serving from 1912 to 1944. Subsequent music directors included Franco Ferrara (1944–1945), Fernando Previtali (1953–1973), and Igor Markevitch (1973–1975). The orchestra was noted for its recordings of Italian opera for the Decca label with such conductors as Tullio Serafin.

Thomas Schippers had been named the next music director to succeed Markevitch, but Schippers died in December 1977, before he could formally assume the post. The music directorship of the orchestra remained vacant until 1983, with the advent of Giuseppe Sinopoli as music director. Sinopoli assisted in restoring the fortunes of the orchestra and expanded the orchestra’s repertoire to include Mahler and Bruckner. Leonard Bernstein was the honorary president of the orchestra from 1983 until 1990.

Antonio Pappano became the orchestra’s music director in 2005. With Pappano, the orchestra has recorded commercially for EMI. Currently, Yuri Temirkanov has the title of honorary conductor of the orchestra.

Sources

- Piano Concerto (Schumann) on Wikipedia

- Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia on Wikipedia

- Piano Concerto, Op.54 (Schumann, Robert) on the International Music Score Library Project website

- Chopin: Scherzo No. 3 [İlyun Bürkev] - September 14, 2024

- César Franck: Violin Sonata [Argerich, Capuçon] - September 8, 2024

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 23 “Appassionata” [Anna Fedorova] - September 7, 2024