Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “Le Nozze di Figaro” (The Marriage of Figaro) with puppets, performed by the Salzburg Marionette Theatre and the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir, conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini.

Performed by the Salzburg Marionette Theatre and the Philarmonic Orchestra and Choir London, conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini

The video above is a 2002 version of the show. Salzburg Marionette Theatre is still staging “The Marriage of Figaro” (with the same orchestration and soloists – the same recordings).

Text and Narrator: Sir Peter Ustinov

Figaro: Giuseppe Taddei (baritone)

Susanna: Anna Moffo (soprano)

Il conte d’Almaviva: Eberhard Waechter (baritone)

La Contessa: Fiorenza Cossotto (mezzo-soprano)

Bartolo: Ivo Vinco (bass)

Marcellina: Dora Gatta

Don Basilio / Don Curzio: Renato Ercolani

Barbarina: Elisabetta Fusco

Antonio: Piero Cappuccilli

Due Ragazze: Gillian Spencer & Diana Gillingham

The Marriage of Figaro

The Marriage of Figaro (Italian: Le

The opera is a cornerstone of the repertoire and appears consistently among the top ten in the Operabase list of most frequently performed operas.

The Marriage of Figaro continues the plot of The Barber of Seville several years

Place: Count Almaviva’s estate, Aguas-Frescas, three leagues outside Seville, Spain.

Act 1

A partly furnished room, with a chair in the center.

Figaro happily measures the space where the bridal bed will fit while Susanna tries on her wedding bonnet in front of a mirror (in the present day, a more traditional French floral wreath or a modern veil are often substituted, often in combination with a bonnet, so as to accommodate what Susanna happily describes as her wedding cappellino). (Duet: Cinque, dieci, venti – “Five, ten, twenty”). Figaro is quite pleased with their new room; Susanna far less so (Duettino: Se a caso madama la notte ti chiama – “If the Countess should call you during the night”). She is bothered by its proximity to the Count’s chambers: it seems he has been making advances toward her and plans on exercising his droit du seigneur, the purported feudal right of a lord to bed a servant girl on her wedding night before her husband can sleep with her. The Count had the right abolished when he married Rosina, but he now wants to reinstate it. Figaro is livid and plans to outwit the Count (Cavatina: Se vuol ballare signor contino – “If you want to dance, sir count”).

Figaro departs, and Dr. Bartolo arrives with Marcellina, his old housekeeper. Marcellina has hired Bartolo as legal counsel, since Figaro had once promised to marry her if he should default on a loan she had made to him, and she intends to enforce that promise. Bartolo, still irked at Figaro for having facilitated the union of the Count and Rosina (in The Barber of Seville), promises, in comical lawyer-speak, to help Marcellina (aria: La vendetta – “Vengeance”).

Bartolo departs, Susanna returns, and Marcellina and Susanna share an exchange of very politely delivered sarcastic insults (duet: Via resti servita, madama brillante – “After you, brilliant madam”). Susanna triumphs in the exchange by congratulating her rival on her impressive age. The older woman departs in a fury.

Cherubino then arrives and, after describing his emerging infatuation with all women, particularly with his “beautiful godmother” the Countess (aria: Non so più cosa son – “I don’t know anymore what I am”), asks for Susanna’s aid with the Count. It seems the Count is angry with Cherubino’s amorous ways, having discovered him with the gardener’s daughter, Barbarina, and plans to punish him. Cherubino wants Susanna to ask the Countess to intercede on his behalf. When the Count appears, Cherubino hides behind a chair, not wanting to be seen alone with Susanna. The Count uses the opportunity of finding Susanna alone to step up his demands for favours from her, including financial inducements to sell herself to him. As Basilio, the music teacher, arrives, the Count, not wanting to be caught alone with Susanna, hides behind the chair. Cherubino leaves that hiding place just in time, and jumps onto the chair while Susanna scrambles to cover him with a dress.

When Basilio starts to gossip about Cherubino’s obvious attraction to the Countess, the Count angrily leaps from his hiding place (terzetto: Cosa

Act 2

A handsome room with an alcove, a dressing room on the left, a door in the background (leading to the servants’ quarters) and a window at the side.

The Countess laments her husband’s infidelity (aria: Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro – “Grant, love, some comfort”). Susanna comes in to prepare the Countess for the day. She responds to the Countess’s questions by telling her that the Count is not trying to seduce her; he is merely offering her a monetary contract in return for her affection. Figaro enters and explains his plan to distract the Count with anonymous letters warning him of adulterers. He has already sent one to the Count (via Basilio) that indicates that the Countess has a rendezvous of her own that evening. They hope that the Count will be too busy looking for imaginary adulterers to interfere with Figaro and Susanna’s wedding. Figaro additionally advises the Countess to keep Cherubino around. She should dress him up as a girl and lure the Count into an illicit rendezvous where he can be caught red-handed. Figaro leaves.

Cherubino arrives, sent in by Figaro and eager to co-operate. Susanna urges him to sing the song he wrote for the Countess (aria: Voi che sapete che cosa è amor – “You ladies who know what love is, is it what I’m suffering from?”). After the song, the Countess, seeing Cherubino’s military commission, notices that the Count was in such a hurry that he forgot to seal it with his signet ring (which would be necessary to make it an official document).

Susanna and the Countess then begin with their plan. Susanna takes off Cherubino´s cloak, and she begins to comb his hair and teach him to behave and walk like a woman (aria of Susanna: Venite, inginocchiatevi – “Come, kneel down before me”). Then she leaves the room through a door at the back to get the dress for Cherubino, taking his cloak with her.

While the Countess and Cherubino are waiting for Susanna to come back, they suddenly hear the Count arriving. Cherubino hides in the closet. The Count demands to be allowed into the room and the Countess reluctantly unlocks the door. The Count enters and hears a noise from the closet. He tries to open it, but it is locked. The Countess tells him it is only Susanna, trying on her wedding dress. At this moment, Susanna re-enters unobserved, quickly realizes what’s going on, and hides behind a couch (Trio: Susanna, or via, sortite – “Susanna, come out!”). The Count shouts for her to identify herself by her voice, but the Countess orders her to be silent. Furious and suspicious, the Count leaves, with the Countess, in search of tools to force the closet door open. As they leave, he locks all the bedroom doors to prevent the intruder from escaping. Cherubino and Susanna emerge from their hiding places, and Cherubino escapes by jumping through the window into the garden. Susanna then takes Cherubino’s former place in the closet, vowing to make the Count look foolish (duet: Aprite, presto, aprite – “Open the door, quickly!”).

The Count and Countess return. The Countess, thinking herself trapped, desperately admits that Cherubino is hidden in the closet. The enraged Count draws his sword, promising to kill Cherubino on the spot, but when the door is opened, they both find to their astonishment only Susanna (Finale: Esci

Act 3

A rich hall, with two thrones, prepared for the wedding ceremony.

The Count mulls over the confusing situation. At the urging of the Countess, Susanna enters and gives a false promise to meet the Count later that night in the garden (duet: Crudel! perchè finora – “Cruel girl, why did you make me wait so long”). As Susanna leaves, the Count overhears her telling Figaro that he has already won the case. Realizing that he is being tricked (recitative and aria: Hai già vinta la causa! … Vedrò, mentr’io sospiro – “You’ve already won the case!” … “Shall I, while sighing, see”), he resolves to punish Figaro by forcing him to marry Marcellina.

Figaro’s hearing follows, and the Count’s judgment is that Figaro must marry Marcellina. Figaro argues that he cannot get married without his parents’ permission, and that he does not know who his parents are, because he was stolen from them when he was a baby. The ensuing discussion reveals that Figaro is Rafaello, the long-lost illegitimate son of Bartolo and Marcellina. A touching scene of reconciliation occurs. During the celebrations, Susanna enters with a payment to release Figaro from his debt to Marcellina. Seeing Figaro and Marcellina in celebration together, Susanna mistakenly believes that Figaro now prefers Marcellina to her. She has a tantrum and slaps Figaro’s face. Marcellina explains, and Susanna, realizing her mistake, joins the celebration. Bartolo, overcome with emotion, agrees to marry Marcellina that evening in a double wedding (sextet: Riconosci in questo amplesso – “Recognize in this embrace”).

All leave, before Barbarina, Antonio’s daughter, invites Cherubino back to her house so they can disguise him as a girl. The Countess, alone, ponders the loss of her happiness (aria: Dove sono i bei momenti – “Where are they, the beautiful moments”). Meanwhile, Antonio informs the Count that Cherubino is not in Seville, but in fact at his house. Susanna enters and updates her mistress regarding the plan to trap the Count. The Countess dictates a love letter for Susanna to send to the Count, which suggests that he meet her (Susanna) that night, “under the pines”. The letter instructs the Count to return the pin which fastens the letter (duet: Sull’aria…che soave zeffiretto – “On the breeze… What a gentle little zephyr”).

A chorus of young peasants, among them Cherubino disguised as a girl, arrives to serenade the Countess. The Count arrives with Antonio and, discovering the page, is enraged. His anger is quickly dispelled by Barbarina, who publicly recalls that he had once offered to give her anything she wants, and asks for Cherubino’s hand in marriage. Thoroughly embarrassed, the Count allows Cherubino to stay.

The act closes with the double wedding, during the course of which Susanna delivers her letter to the Count (Finale: Ecco la marcia – “Here is the procession”). Figaro watches the Count prick his finger on the pin, and laughs, unaware that the love-note is an invitation for the Count to tryst with Figaro’s own bride Susanna. As the curtain drops, the two newlywed couples rejoice.

Act 4

The garden, with two pavilions. Night.

Following the directions in the letter, the Count has sent the pin back to Susanna, giving it to Barbarina. Unfortunately, Barbarina has lost it (aria: L’ho perduta, me meschina – “I have lost it, poor me”). Figaro and Marcellina see Barbarina, and Figaro asks her what she is doing. When he hears the pin is Susanna’s, he is overcome with jealousy, especially as he recognises the pin to be the one that fastened the letter to the Count. Thinking that Susanna is meeting the Count behind his back, Figaro complains to his mother, and swears to be avenged on the Count and Susanna, and on all unfaithful wives. Marcellina urges caution, but Figaro will not listen. Figaro rushes off, and Marcellina resolves to inform Susanna of Figaro’s intentions. Marcellina sings an aria lamenting that male and female wild beasts get along with each other, but rational humans can’t (aria: Il capro e la capretta – “The billy-goat and the she-goat”). (This aria and Basilio’s ensuing aria are usually omitted from performances due to their relative unimportance, both musically and dramatically; however, some recordings include them.)

Motivated by jealousy, Figaro tells Bartolo and Basilio to come to his aid when he gives the signal. Basilio comments on Figaro’s foolishness and claims he was once as frivolous as Figaro was. He tells a tale of how he was given common sense by “Donna Flemma” (“Dame Prudence”) and learned the importance of not crossing powerful people. (aria: In quegli anni – “In those years”). They exit, leaving Figaro alone. Figaro muses bitterly on the inconstancy of women (recitative and aria: Tutto è disposto … Aprite un po’ quegli occhi – “Everything is ready … Open those eyes a little”). Susanna and the Countess arrive, each dressed in the other’s clothes. Marcellina is with them, having informed Susanna of Figaro’s suspicions and plans. After they discuss the plan, Marcellina and the Countess leave, and Susanna teases Figaro by singing a love song to her beloved within Figaro’s hearing (aria: Deh vieni, non tardar – “Oh come, don’t delay”). Figaro is hiding behind a bush and, thinking the song is for the Count, becomes increasingly jealous.

The Countess arrives in Susanna’s dress. Cherubino shows up and starts teasing “Susanna” (really the Countess), endangering the plan. (Finale: Pian pianin le andrò più presso – “Softly, softly I’ll approach her”) Fortunately, the Count gets rid of him by striking out in the dark. His punch actually ends up hitting Figaro, but the point is made and Cherubino runs off.

The Count now begins making earnest love to “Susanna” (really the Countess), and gives her a jeweled ring. They go offstage together, where the Countess dodges him, hiding in the dark. Onstage, meanwhile, the real Susanna enters, wearing the Countess’ clothes. Figaro mistakes her for the real Countess, and starts to tell her of the Count’s intentions, but he suddenly recognizes his bride in disguise. He plays along with the joke by pretending to be in love with “my lady”, and inviting her to make love right then and there. Susanna, fooled, loses her temper and slaps him many times. Figaro finally lets on that he has recognized Susanna’s voice, and they make peace, resolving to conclude the comedy together (Pace, pace, mio dolce tesoro – “Peace, peace, my sweet treasure”).

The Count, unable to find “Susanna”, enters frustrated. Figaro gets his attention by loudly declaring his love for “the Countess” (really Susanna). The enraged Count calls for his people and for weapons: his servant is seducing his wife. (Ultima Scena: Gente, gente, all’armi, all’armi – “Gentlemen, to arms!”) Bartolo, Basilio and Antonio enter with torches as, one by one, the Count drags out Cherubino, Barbarina, Marcellina and the “Countess” from behind the pavilion.

All beg him to forgive Figaro and the “Countess”, but he loudly refuses, repeating “no” at the top of his voice, until finally the real Countess re-enters and reveals her true identity. The Count, seeing the ring he had given her, realizes that the supposed Susanna he was trying to seduce was actually his wife. Ashamed and remorseful, he kneels and pleads for forgiveness himself (Contessa perdono! – “Countess, forgive me!”). The Countess, more kind than he (Più docile io sono – “I am more mild”), forgives her husband and all are contented. The opera ends in universal celebration.

Salzburg Marionette Theatre

Salzburg Marionette Theatre, with their words, is “a large theater with small “actors” and a wide and varied repertoire which has charmed countless children and adults for a century, and has become famous throughout the world”.

They present operas by various composers, including Mozart’s Magic Flute and The Marriage of Figaro, as well as the Salzburg classic The Sound of Music, Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker ballet and Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream or Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince.

Peter Ustinov

Sir Peter Ustinov (16 April 1921 – 28 March 2004) was an English actor, writer, dramatist, filmmaker, theatre and opera director, stage designer, screenwriter, comedian, humorist, newspaper and magazine columnist, radio broadcaster, and television presenter. He was a fixture on television talk shows and lecture circuits for much of his career. A respected intellectual and diplomat, he held various academic posts and served as a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF and President of the World Federalist Movement.

Ustinov was the winner of numerous awards over his life, including two Academy Awards for Best Supporting Actor, Emmy Awards, Golden Globes and BAFTA Awards for acting, and a Grammy Award for best recording for children, as well as the recipient of governmental honours from, amongst others, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. He displayed a unique cultural versatility that has frequently earned him the accolade of a Renaissance man. Miklós Rózsa, composer of the music for Quo Vadis and of numerous concert works, dedicated his String Quartet No. 1, Op. 22 (1950) to Ustinov.

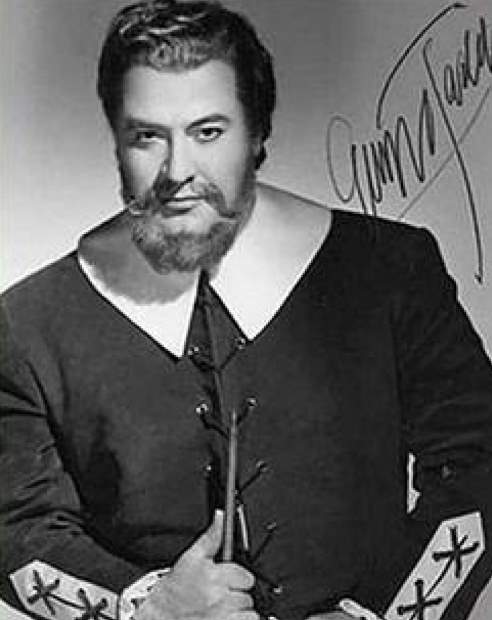

Giuseppe Taddei

Giuseppe Taddei (26 June 1916 – 2 June 2010) was an Italian lyric baritone, who performed mostly the operas of Mozart and Verdi. Taddei left many recordings, notably as Figaro in The Marriage of Figaro and Leporello in Don Giovanni in the Carlo Maria Giulini renditions, as Macbeth, opposite Birgit Nilsson, in Macbeth, conducted by Thomas Schippers, and as Scarpia in Tosca and as Falstaff in Falstaff, both conducted by Herbert von Karajan.

Anna Moffo

Anna Moffo (June 27, 1932 – March 9, 2006) was an American opera singer, television personality, and award-winning dramatic actress. One of the leading lyric-coloratura sopranos of her generation, she possessed a warm and radiant voice of considerable range and agility. Noted for her physical beauty, she was nicknamed “La Bellissima” (the beautiful).

Eberhard Waechter

Eberhard Waechter (the engraving on his gravestone is Waechter, different from his family “von Wächter”) (9 July 1929 – 29 March 1992) was an Austrian baritone celebrated for his performances in the operas of Mozart, Richard Wagner, and Richard Strauss. After retiring from singing, he became Intendant of the Vienna Volksoper and the Vienna State Opera.

Fiorenza Cossotto

Fiorenza Cossotto (born April 22, 1935) is an Italian mezzo-soprano. She is considered by many to be one of the greatest mezzo-sopranos of the 20th century.

Fiorenza sang with Maria Callas as early as 1957 in Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, and many times later, until Callas’ last Norma in Paris. The last performance of the latter was truncated when Callas’ walked out right after their quintessential duet, “Mira, o Norma.” Some claim that Cossotto intentionally sabotaged Callas by singing over her and holding high notes longer with the latter’s voice (by that time, 1965) past its prime and in poor form. Others claim, in favor of Cossotto, that she encouraged Callas to sing as best as she could, and was quite cautious with her and tried to give her as much support as she could.

Cossotto on the subject:

“But look, it’s a disgrace! It’s been forty years, and books still come out speaking ill of me. The first year we did our rehearsals, and everything went well. Callas was in good voice. There was no reason for her not to do Norma, which was her warhorse. During the last two performances [in 1965], she was not well — she had a cold, which passed down [into the chest]. The last performance, poor thing, she couldn’t say no, because all Onassis’s elite [retinue] was in the theater. But logically she couldn’t [sing

“Later, Callas, at the end of the second act, said to me, ‘Fiorenza, stay tonight until the end because I am not well, and we will all go out [to take curtain calls and bow] together.’ We’ll make a bit of a good impression, is what she wanted to say. ‘Look,’ I said, ‘I can’t

Simionato’s claim:

“…she (Callas) asked me to sing with her in two of her final performances of Norma [in Paris], for her other partner (Fiorenza Cossotto) had been behaving inconsiderately.”

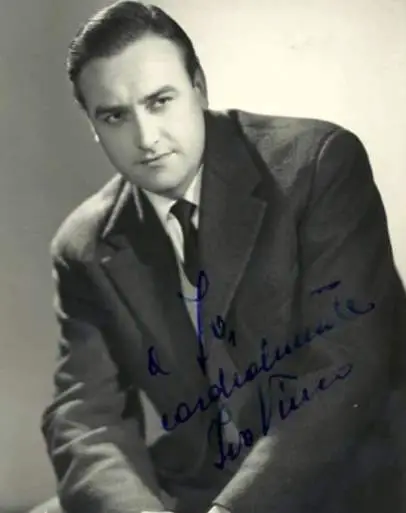

Ivo Vinco

Ivo Vinco (8 November 1927 – 8 June 2014) was an Italian bass opera singer. He sang all the great bass roles of the Italian repertory notably; Oroveso, Raimondo, Sparafucile, Ferrando, Fiesco, Padre Guardiano, Gran Inquisitore, Alvise, etc. He was married for a time to mezzo-soprano Fiorenza Cossotto, with whom he had a son, Roberto.

Sources

- The Marriage of Figaro on Wikipedia

- Salzburg Marionette Theatre web site:

marionetten .at - Peter Ustinov on Wikipedia

- Giuseppe Taddei on Wikipedia

- Anna Moffo on Wikipedia

- Eberhard Waechter on Wikipedia

- Fiorenza Cossotto on Wikipedia

- Ivo Vinco on W

ikipedia