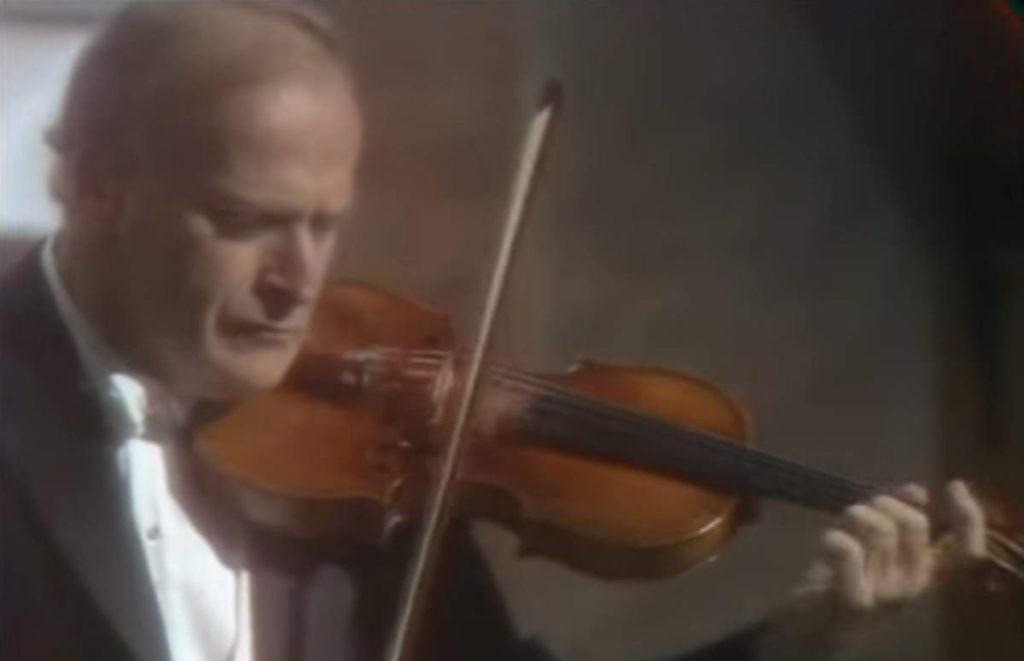

Accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra, widely considered one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, Yehudi Menuhin performs Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61. Conductor: Sir Colin Davis. This 1962 filmed performance is a treasure of classical music, and was a specially recorded performance at BBC TV Center for their series “International Concert Hall”. The recording took place on 22 April 1962, Menuhin’s 46th birthday. The concertmaster (leader) was Hugh Maguire (2 August 1926 – 14 June 2013), the Irish violinist, leader, concertmaster, and principal player of the London Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Symphony Orchestra (1962-1967).

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, is a cornerstone of the violin repertoire and one of the most revered violin concertos in classical music. Composed in 1806, it is Beethoven’s only concerto for violin and showcases a profound depth of musical expression combined with technical sophistication.

The genesis of the concerto is linked to Beethoven’s relationship with Franz Clement, a leading violinist of the day, who is believed to have been the work’s dedicatee and its first performer. Despite its eventual iconic status, the concerto initially received a lukewarm response at its premiere, which took place at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna in 1806. This tepid reception was possibly due to the concerto’s subtle approach to virtuosity and its demands for a high degree of interpretative insight from the soloist, which may not have been fully appreciated at the time.

Musically, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is noted for its lyrical beauty, structural coherence, and the delicate balance it strikes between the soloist and the orchestra. The concerto opens up new dimensions in the interplay between solo violin and orchestral accompaniment, moving away from the showy, virtuosic style of many earlier concerti. Instead, it demands a deep musical understanding and a refined technique from the soloist, who must weave together the intricate dialogue with the orchestra.

The concerto is distinguished by its expansive structure and the innovative use of the violin, which is treated more lyrically than in many previous works. Beethoven’s writing allows the violin to sing, with long, flowing lines and generous melodic passages that explore the instrument’s expressive capabilities. The orchestration supports this, providing a rich, but never overpowering, backdrop that includes moments of tender interaction as well as powerful, dramatic statements.

Despite its initial reception, the concerto gradually gained fame, significantly aided by the efforts of violinist Joseph Joachim in the mid-19th century. Joachim’s advocacy for the piece, including his performances and his cadenza, which has become one of the most frequently performed, helped establish the concerto as a staple of the violin repertoire.

Today, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is celebrated for its depth and beauty, often regarded as an epitome of the violin concerto form. It remains a profound testament to Beethoven’s genius, combining technical mastery with deep emotional resonance, making it a beloved challenge for violinists and a favorite among audiences worldwide.

Movements

1. Allegro ma non troppo

The first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, titled “Allegro ma non troppo,” is a sublime example of musical architecture and expressive depth, renowned for its elegance and breadth. This opening movement sets the stage for the entire concerto, establishing a dialogue between the solo violin and the orchestra that is both intimate and grand.

The movement begins with a long orchestral introduction, which is characteristic of Beethoven’s concertos. This introduction sets forth the primary thematic material, starting with five soft timpani beats that become a rhythmic motif throughout the movement. These beats lead into a serene and expansive melody played by the woodwinds and strings. The introduction alone lasts several minutes, creating a rich harmonic and melodic foundation before the violin even enters.

When the violin does enter, it does so with a quiet but profound statement, gradually building its presence. The solo part is lyrical and demands a wide range of expression from the violinist. Beethoven moves away from the flashy virtuosity typical of many violin concertos of the time, instead opting for a style that requires the soloist to interweave with the orchestra, contributing to the overall musical narrative rather than dominating it.

The development section of the movement is a masterclass in thematic transformation and orchestration. Here, Beethoven explores and manipulates the themes introduced earlier, demonstrating his skill in developing motifs and building tension. The interaction between the solo violin and the orchestra becomes more intense and intricate, with the violin often soaring above rich orchestral textures.

The recapitulation brings back the main themes, now colored by the journey of the development. The solo violin reasserts these themes with renewed vigor and leads to a cadenza. Traditionally, this cadenza is an opportunity for the violinist to showcase technical skill and personal interpretation. The cadenza was not originally written by Beethoven; instead, the soloist was expected to improvise or compose their own. Today, many performers choose to play cadenzas written by famous violinists such as Joachim or Kreisler.

The movement concludes with a reprise of the main themes and a final orchestral tutti, which reaffirms the tonal and thematic material of the movement, ending in a satisfying and majestic closure.

2. Larghetto

The second movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, titled “Larghetto,” is a tranquil and deeply expressive movement that offers a poignant contrast to the dynamic and expansive first movement. This movement exemplifies Beethoven’s ability to convey profound emotion through simple and elegant means.

The “Larghetto” opens with the orchestra setting a gentle, serene atmosphere. The orchestration is subdued, providing a soft cushion of sound over which the violin can sing. The movement is structured in a loose sonata form, focusing primarily on the lyrical interplay between the solo violin and the orchestral accompaniment. The violin part is characterized by long, flowing lines that require great control and expressiveness from the soloist. The emphasis here is on melody and emotion rather than technical display.

The solo violin enters with a theme that is both sweet and melancholic, weaving through the orchestral texture with grace and subtlety. The theme is expansive, stretching out in long, arching phrases that showcase the violin’s capacity for sustained singing. This melodic material is delicately ornamented, adding layers of nuance and depth to the simple line.

Throughout the movement, the dialogue between the violin and orchestra is intimate and conversational. The orchestration remains light, with woodwinds and strings providing a responsive and tender backdrop to the violin’s explorations. The interaction often feels like a gentle exchange of thoughts between old friends, each phrase answered by a loving echo.

As the movement progresses, the melody is passed back and forth between the soloist and different sections of the orchestra, creating a rich tapestry of sound. The central section of the movement develops the main theme further, exploring different harmonic and textural possibilities before returning to the tranquil mood of the opening.

The conclusion of the “Larghetto” is reflective and subdued, with the violin gradually receding into the orchestral texture, allowing the movement to end quietly and without resolution. This unresolved ending serves as a perfect segue into the spirited final movement, creating a sense of anticipation and continuity within the concerto.

3. Rondo. Allegro

The third movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, titled “Rondo: Allegro,” serves as a lively and spirited finale to the concerto. This movement is characterized by its rhythmic energy, playful interaction between the solo violin and the orchestra, and a joyful, dance-like quality that contrasts with the serene and introspective second movement.

Structured as a rondo, the movement revolves around a main theme that returns several times, interspersed with contrasting episodes. The rondo theme is catchy and rhythmic, featuring a buoyant, skipping rhythm that gives it a distinctly jubilant character. This theme is first introduced by the orchestra and then quickly taken up by the solo violin, which elaborates on it with virtuosic flourishes and playful runs.

The violin part in this movement is notably more virtuosic than in the previous movements, showcasing the soloist’s technical skills and interpretative flair. The soloist engages in a vibrant dialogue with the orchestra, responding to and expanding upon the thematic material presented by the ensemble. The movement’s structure allows for a dynamic interplay between predictability and surprise, with the recurring rondo theme anchoring the movement’s progress while the episodes offer fresh musical ideas and textures.

Each episode introduces new material that contrasts with the rondo theme in mood, key, or texture, providing variety and maintaining listener interest. These sections often explore different emotional or dramatic territories, allowing the soloist to display a range of expressive capabilities. Beethoven uses these episodes to delve into more lyrical or dramatic themes, which the soloist interprets with depth and sensitivity.

The orchestration in the third movement is vibrant and colorful, supporting the soloist with a lively and responsive backdrop. The orchestra’s role is not just accompaniment but an integral part of the musical conversation, with the wind and brass sections particularly contributing to the festive and robust atmosphere.

The movement builds towards a climactic conclusion, with the rondo theme returning for a final, triumphant appearance. Beethoven crafts an exhilarating finale, featuring a brilliant cadenza (often the soloist’s choice or a standard one by a famous violinist) that leads directly into the final orchestral tutti. This closing passage reiterates the rondo theme in a grand and celebratory manner, bringing the concerto to an exuberant and satisfying close.

Sources

- Violin Concerto (Beethoven) on Wikipedia

- Violin Concerto in D major, Op.61 (Beethoven, Ludwig van) on the International Music Score Library Project website

- Beethoven’s Violin Concerto on the Classical Notes website