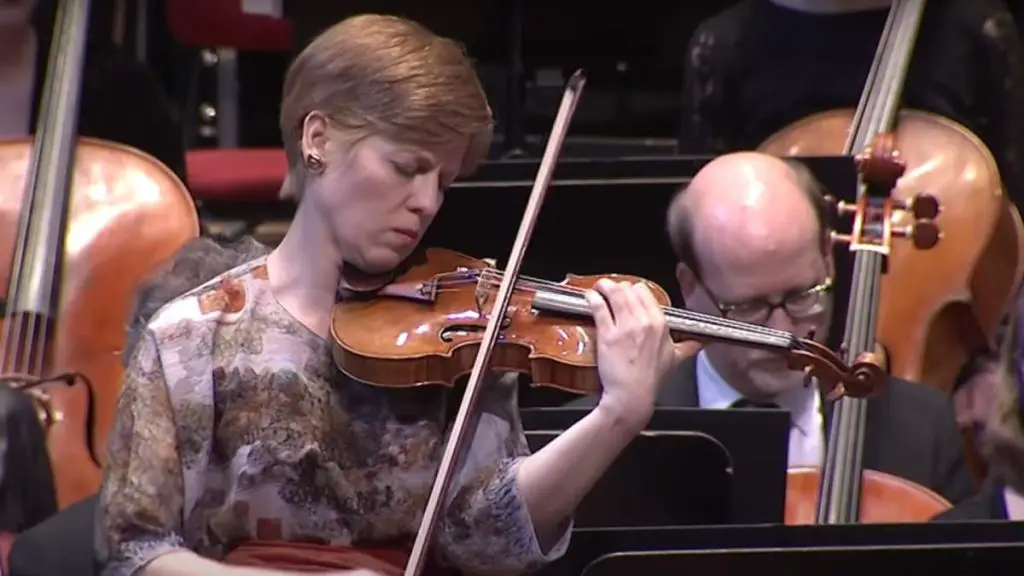

Accompanied by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the great Polish violinist Henryk Szeryng performs Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61. Conductor: Jorge Mester. This recording showcases Szeryng’s outstanding technical and expressive skills, making it a valuable rendition for enthusiasts of classical music and violin performances.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61, is a cornerstone in the violin repertoire, celebrated for its lyrical beauty and profound depth. Written in 1806, the concerto was first performed by Franz Clement, a close friend and esteemed violinist of the time. Despite its initial lukewarm reception, the piece eventually gained recognition as a masterpiece, thanks in large part to the advocacy and brilliant interpretations of famous violinists in the subsequent centuries.

The concerto, characterized by its expansive form and the delicate interplay between the solo violin and the orchestra, exemplifies Beethoven’s innovative approach to the concerto genre. It opens with a lengthy orchestral introduction, creating a broad sonic canvas, before introducing the solo violin. Throughout, the piece offers a perfect balance of drama and lyricism, intricate details, and sweeping musical gestures.

The Beethoven Violin Concerto is noted for its demands on the soloist, requiring not only technical proficiency but also deep musicality and the ability to convey the piece’s wide emotional range. Over time, it has become a rite of passage for accomplished violinists, serving as a testament to their mastery of the instrument and understanding of classical music’s expressive possibilities.

This concerto has inspired countless musicians and has been the subject of numerous recordings, each interpreter bringing their unique perspective and insight to the timeless score. The enduring appeal of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto lies in its combination of virtuosity and depth, providing both performers and audiences with an endlessly rewarding musical experience. Whether experienced live in concert or through recordings, the concerto continues to captivate with its sheer beauty and emotional resonance.

Movements

1. Allegro ma non troppo

The first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61, is marked “Allegro ma non troppo,” which means “fast, but not too much.” It is an exquisite example of the Classical concerto form, incorporating a meticulous structure with expressive depth, engaging both the soloist and orchestra in a dynamic conversation.

This movement begins with four beats of the timpani, establishing a rhythmic motif that reappears throughout. The orchestra then introduces the main themes, which are extensive and lyrical, demonstrating a delicate balance of grace and grandiosity. These themes are characterized by their sweeping melodic lines and dynamic contrasts, providing a foundation upon which the entire movement builds.

The solo violin makes its entrance after the orchestral exposition, reiterating and elaborating on the themes introduced by the orchestra. The violin part is technically demanding, featuring a wide range of techniques including rapid scales, arpeggios, double stops, and lyrical melodic passages. Despite the technical challenges, the soloist is also required to convey the emotional depth and subtlety inherent in the music, engaging in a dialogue with the orchestra that is both intimate and expansive.

A cadenza, typically an improvised or composed solo passage allowing the soloist to display their virtuosity, is also a crucial aspect of the first movement. The cadenza offers the performer an opportunity to showcase not only technical skill but also interpretative insight, as it often encapsulates and reflects upon the themes of the movement.

The first movement concludes with a reprise of the primary themes by the orchestra and soloist, culminating in a final, emphatic statement that beautifully rounds off this section of the concerto. Overall, the Allegro ma non troppo combines virtuosity with a profound emotional core, embodying the innovative spirit and enduring appeal of Beethoven’s musical genius.

2. Larghetto

The second movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, marked “Larghetto,” presents a sharp contrast to the first, embodying a serene, lyrical, and contemplative character. This movement is shorter and slower than the first, offering listeners a moment of repose and reflection in the midst of the concerto’s broader narrative.

“Larghetto” is indicative of a slow tempo, and in this movement, Beethoven crafts a serene and tender atmosphere through the use of simple, yet deeply expressive, melodic lines and harmonies. It opens with the orchestra introducing a gentle, singing theme, with the strings providing a lush, supportive backdrop.

The solo violin enters with a response to the orchestra’s theme, spinning out elaborations and variations with an exquisite, singing tone. Throughout the movement, the soloist engages in a delicate dialogue with the orchestra, weaving in and out of the texture with grace and sensitivity. The music unfolds with a sense of introspection and tranquility, as the violin and orchestra exchange and develop the thematic material.

The second movement doesn’t possess the overt virtuosity found in the outer movements; instead, it requires the soloist to demonstrate refined control, nuance, and a deep sense of musicality to convey the movement’s subtle beauty and emotive depth. The Larghetto serves as a peaceful interlude before the energetic finale, captivating audiences with its lyricism and the intimate conversation between the solo violin and the ensemble.

Beethoven seamlessly transitions from the second movement to the third without a break, maintaining a sense of continuity and flow within the concerto. The Larghetto’s tranquil and reflective mood sets the stage for the spirited and joyful character of the final movement, providing a balanced and satisfying overall structure to this masterful work.

3. Rondo. Allegro

The finale of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61, is marked “Rondo: Allegro,” and it is characterized by its lively, joyful, and dance-like nature. As implied by the term “Rondo”, this movement follows a recurring theme structure, in which a principal theme alternates with secondary themes, providing a sense of familiarity and cohesiveness while also offering contrast and variety in the musical material.

The main theme of the Rondo is introduced by the solo violin, a bright and spirited melody that carries a sense of playfulness and exuberance. This theme is catchy and rhythmic, immediately capturing the listener’s attention and setting the tone for the remainder of the movement. The soloist’s part is virtuosic and dynamic, showcasing rapid passages, nimble articulations, and expressive nuances, requiring both technical mastery and a deep sense of musicality from the performer.

As the movement progresses, the main theme is interspersed with contrasting episodes, often introduced by the orchestra, which provide different moods and textures. These episodes offer a dialogue between the solo violin and the orchestra, engaging in a musical conversation that is at times tender, at times dramatic, but always engaging and captivating. The alternation between the lively main theme and the contrasting sections creates a sense of tension and release, driving the movement forward with energy and excitement.

Towards the end of the movement, it is traditional for the soloist to perform a cadenza, although the cadenza in this movement is typically shorter and less improvisatory than that in the first. This final cadenza allows the soloist one last opportunity to display their technical prowess and interpretative insight before the concerto concludes.

The movement ends with a return to the joyful main theme, building up to a thrilling and triumphant conclusion. The third movement’s spirited character and infectious melody leave a lasting impression on listeners, providing a fitting and celebratory close to Beethoven’s monumental Violin Concerto.

Henryk Szeryng

Henryk Szeryng was a renowned Polish violinist and composer, celebrated for his impeccable technique, rich tone, and interpretative mastery. Born on September 22, 1918, in Zelazowa Wola, Poland, Szeryng began studying the violin at a very young age, showing prodigious talent.

Szeryng’s early musical education took place in Berlin, where he studied with Carl Flesch. Later, he moved to Paris to study with Jacques Thibaud. His education was not only confined to music, as he was a polyglot, speaking seven languages, which testified to his intellectual curiosity and broad interests.

His career was temporarily interrupted by World War II. During the war, Szeryng worked with the Polish government in exile and gave concerts for Allied troops, for which he was recognized and honored by the governments of France, Poland, and Belgium.

After the war, Szeryng’s international career as a concert violinist took off. He performed with major orchestras worldwide, collaborating with illustrious conductors and other leading musicians of his time. In addition to his performing career, Szeryng was dedicated to education, holding teaching positions at various institutions, and was known for his generous support of young musicians.

Szeryng’s extensive discography includes masterful interpretations of a wide range of the violin repertoire, from Baroque to Romantic to 20th-century works. His recordings of works by composers like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, and others have been critically acclaimed for their clarity, expressivity, and technical finesse.

The violinist was also a cultural ambassador. He took Mexican citizenship in 1946 and worked diligently to promote classical music in Mexico and beyond, further enriching the cultural landscape of his adopted country.

Henryk Szeryng passed away on March 8, 1988, leaving behind a legacy of recordings, students, and contributions to the world of classical music. His artistry continues to inspire violinists and music lovers around the world, celebrating him as one of the foremost musicians of the 20th century.

Sources

- Violin Concerto (Beethoven) on Wikipedia