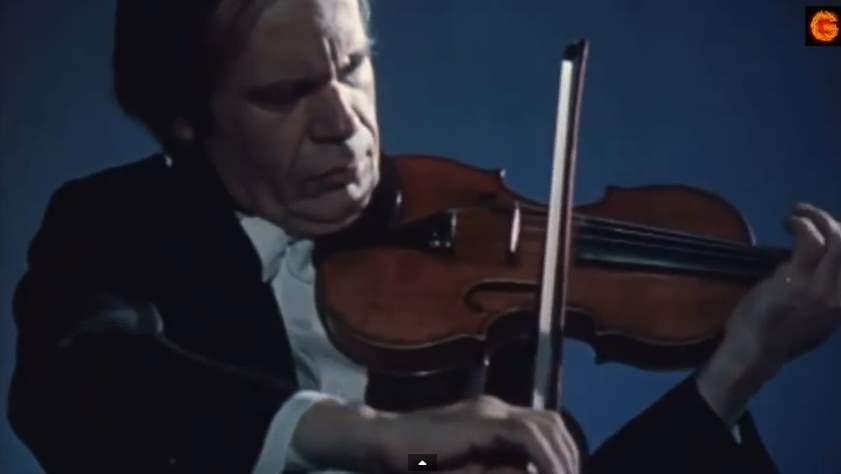

Accompanied by the Nouvel Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, a preeminent Soviet violinist of the 20th century, Leonid Kogan performs Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61. Conductor: Emmanuel Krivine. Encore: Johann Sebastian Bach: Sarabande from the Violin Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004. This performance was recorded at the Grand Auditorium, Maison de la Radio, Paris on February 18, 1977.

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, holds a significant place in the violin repertoire and in the history of classical music. Composed in 1806, it is Beethoven’s only concerto for violin and is widely regarded as one of the most important works in the violin concerto genre. This concerto reflects a pivotal period in Beethoven’s life, where he was grappling with the onset of deafness, yet it exudes a sense of profound depth and serene beauty.

Beethoven composed this concerto for his colleague Franz Clement, a leading violinist of the day. The work premiered on December 23, 1806, in Vienna. Interestingly, the concerto was reportedly finished so close to the premiere that Clement had to perform parts of it without much preparation, allegedly sight-reading some sections. This highlights both Clement’s remarkable skill and the challenging nature of the concerto.

The concerto is characterized by its lyrical qualities, expansive structure, and the delicate interplay between the solo violin and the orchestra. Unlike many concertos of the time, which often showcased the virtuosity of the soloist, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto places greater emphasis on musical expression and thematic development. This approach was somewhat innovative for its time and helped pave the way for the romantic concerto style.

Despite its initial lukewarm reception, the concerto eventually gained immense popularity and critical acclaim, particularly after the violinist Joseph Joachim performed it in London in 1844, with Felix Mendelssohn conducting. This performance is often credited with reviving interest in the concerto and establishing its place in the standard violin repertoire.

The work is notable for its use of the timpani, which is introduced in the very first bars and sets a rhythmic motif that recurs throughout the piece. The orchestration is balanced and elegant, allowing the violin to shine without overwhelming it. The concerto’s thematic material is characterized by its melodic richness and emotional depth, traversing a wide range of moods and colors.

Beethoven’s only violin concerto stands as a masterpiece of the classical repertoire, notable for its lyrical beauty, innovative approach to the concerto form, and significant role in the evolution of violin music. Its influence can be seen in the works of many later composers who sought to emulate its depth and expressiveness in their own concertos.

Movements

1. Allegro ma non troppo

The first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, is marked Allegro ma non troppo, meaning fast but not overly so. This movement, with its expansive length and profound musical depth, sets the tone for the entire concerto.

The movement opens with a distinctive timpani motif, a series of soft, rhythmic beats that introduce a theme of understated yet compelling significance. This motif, played by the kettledrums, is a unique feature in the concerto repertoire and becomes a unifying element throughout the movement. The orchestra then takes over, introducing the main thematic material in a lengthy exposition, characterized by its lyrical and expansive melodies.

After the orchestral introduction, the violin enters, not with a grand statement, but rather with a gentle and almost introspective theme. This entrance marks a departure from the virtuosic displays typical of many concerti of the time, emphasizing musical expression over showmanship. The violin part weaves through intricate passages and beautiful melodies, showcasing the instrument’s range and the soloist’s technical skill.

The development section of the movement is where Beethoven’s mastery of form and thematic development truly shines. Here, he takes the themes introduced in the exposition and explores them further, modulating through different keys and creating a rich tapestry of sound. This section highlights the interplay between the soloist and the orchestra, with each responding to and elaborating on the other’s ideas.

The cadenza, traditionally an improvised or composed solo passage for the violin, is a focal point of the movement. In many performances, the cadenza used is one that was written by Beethoven himself, albeit for a later arrangement of the concerto for piano. This cadenza allows the soloist to showcase their technical prowess and interpretive skills, serving as a bridge to the recapitulation.

The recapitulation brings back the main themes, now transformed and enriched by their journey through the development section. The movement concludes with a coda, which revisits the opening timpani motif and brings the movement to a majestic close.

Throughout the first movement, Beethoven’s use of harmony, melody, and orchestration demonstrates a sublime balance between the solo violin and the orchestra, creating a dialogue that is both intimate and grand. This movement, with its emotional depth and technical brilliance, is a testament to Beethoven’s genius and a cornerstone of the violin repertoire.

2. Larghetto

The second movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, marked Larghetto, is a serene and lyrical contrast to the energetic and expansive first movement. It provides a moment of calm introspection and tender beauty in the concerto.

Characterized by its gentle, flowing melodies, the Larghetto is set in a tranquil and song-like style. This movement is a showcase of Beethoven’s ability to create profound emotional depth through simplicity and lyrical expression. Unlike the dramatic and technically challenging first movement, the second movement focuses on the expressive capabilities of the violin, with long, singing lines that demand a deep sense of musicality and phrasing from the soloist.

The movement opens with a delicate orchestral introduction, setting a mood of peaceful contemplation. The violin enters with a theme that is both sweet and melancholic, weaving through a series of variations. Each variation explores a different aspect of the theme, with subtle changes in dynamics, articulation, and ornamentation. The solo violin is often accompanied by a soft, cushioned background provided by the orchestra, creating an intimate musical conversation.

One of the remarkable features of this movement is its restraint and understatement. Beethoven avoids overt displays of virtuosity, focusing instead on the purity of melody and the emotional resonance of the music. The violin line is lyrical and expressive, requiring a level of control and sensitivity from the performer to convey the nuances of the music effectively.

The orchestration in this movement is delicate and carefully balanced, allowing the solo violin to shine without being overshadowed. The use of winds and strings in the orchestra adds color and depth to the texture, complementing the solo line without competing with it.

As the movement progresses, it builds to a gentle climax before returning to the peaceful mood of the opening. The Larghetto concludes softly, creating a seamless transition into the final movement of the concerto. This movement, with its quiet beauty and emotional depth, is a key part of the concerto’s overall structure, providing a reflective and introspective heart to the work.

3. Rondo. Allegro

The finale of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, is marked Rondo: Allegro. This movement is characterized by its lively, spirited nature and serves as a vivacious conclusion to the concerto.

Rondo form, typical of final movements in classical concertos, involves a recurring main theme (the “refrain”) alternating with contrasting sections (the “episodes”). Beethoven’s Rondo in this concerto is a fine example of this structure, showcasing both rhythmic vitality and thematic ingenuity.

The movement begins with the orchestra introducing the rondo theme, a playful and energetic melody that sets the tone for the rest of the movement. This theme is catchy and rhythmic, with a dance-like quality that brings a sense of joy and exuberance. When the solo violin enters, it takes up this theme, adding its own flair and virtuosity.

The episodes that intersperse the recurring rondo theme offer contrasts in mood and texture. They explore different keys, dynamics, and orchestral colors, providing the soloist with opportunities to display a range of emotions and technical skills. These sections often feature more lyrical and expressive music, offering a momentary respite from the high-spirited energy of the main theme.

One of the highlights of this movement is the interplay between the solo violin and the orchestra. The violin often leads with the thematic material, which is then echoed and developed by the orchestra. This back-and-forth creates a dynamic and engaging musical conversation, a hallmark of Beethoven’s concerto writing.

The technical demands on the soloist in this movement are significant. The violin part is filled with rapid passages, intricate figurations, and high-flying leaps, all requiring agility, precision, and a strong sense of rhythm. Despite these challenges, the movement maintains an overall sense of playfulness and joy.

Towards the end of the movement, there is typically a cadenza, allowing the soloist a final display of virtuosity. This leads to a spirited coda, which revisits the rondo theme and brings the concerto to a triumphant and exhilarating close.

The third movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is a masterful blend of technical brilliance and joyful expression. It perfectly balances the introspective depth of the earlier movements with a sense of celebration and jubilation, concluding the concerto on a high note.

Leonid Kogan

The outstanding Russian violinist and pedagogue, Leonid Borisovich Kogan, was the son of a photographer who was an amateur violinist. After showing an early interest in and ability to play the violin, his family moved to Moscow, where he was able to further his studies. When he was 10 years old, the family moved to Moscow, where he became a pupil of the noted violin pedagogue Abram Yampolsky, first at the Central Music School (1934-1943), then at the Moscow Conservatory (1943-1948), and subsequently he pursued postgraduate studies with him (1948-1951).

In 1934, Jascha Heifetz played concerts in Moscow. “I attended everyone,” Leonid Kogan later said, “and I can remember every note he played until now. He was the ideal artist for me.” When Kogan was 12, Jacques Thibaud was in Moscow and heard him play. The French virtuoso predicted a great future for Kogan. His official debut was in 1941, playing Johannes Brahms’ Violin Concerto with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory.

![Leonid Kogan performs Beethoven Violin Concerto [1977]](https://cdn-0.andantemoderato.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Leonid-Kogan-perorms-Beethoven-Violin-Concerto-1977-1024x576.jpg)

In 1947, Leonid Kogan was co-winner of the first prize at the World Festival of Democratic Youth in Prague. In 1951 he won first prize at the Queen Elizabeth Competition in Brussels with a dazzling performance of Paganini’s first concerto that included an outstanding interpretation of Sauret’s cadenza. His career was instantly assured. Hae played in Europe to unanimous acclaim. His international solo tours took him to Paris and London in 1955, and then to South America and the USA. He made an auspicious American debut playing J. Brahms’ Violin Concerto with Pierre Monteux and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on January 10, 1958.

In 1952, Leonid Kogan began teaching at the Moscow Conservatory; he was named Professor in 1953 and head of the violin department in 1969. Among his pupils, there were Andrew Korsakov and Viktoria Mullova. In 1980 he was invited to teach at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena, Italy. He was made an Honoured Artist in 1955 and a People’s Artist of the USSR in 1964. He received the Lenin Prize in 1965.

Leonid Kogan is considered to have been one of the greatest representatives of the Soviet School of violin playing, an emotionally romantic elan and melodious filigree of technical detail. His career was always overshadowed by that of David Oistrakh, who was strongly promoted by the Soviet authorities.

Leonid Kogan married Elizabeth Gilels (sister of pianist Emil Gilels), who was also a concert violinist. His son, Pavel Kogan (b 1952) became a famous violinist and conductor. His daughter, Nina Kogan (b 1954), is a concert pianist and became the accompanist and sonata partner of her father at an early age. Kogan was Jewish. He died of a heart attack in the city of Mytishchi while traveling by train between Moscow and Yaroslavl to a concert he was to perform with his son. Two days before, he had played Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in Vienna.

Many speculate that Leonid Kogan played on all steel strings, though there is not an outright confirmation. While his close associates indicate he played on gut strings with a steel ‘e’, it is most likely that he used different combinations throughout his career. Kogan used two Guarneri del Gesù violins: the 1726 ex-Colin and the 1733 ex-Burmester. He used French bows by Dominique Peccatte.

Leonid Kogan formed a Trio with pianist Emil Gilels and cellist Rostropovich. Their recordings include Ludwig Van Beethoven’s Archduke Trio, Robert Schumann’s D minor Trio, Tchaikovsky’s Trio, Camille Saint-Saëns’ Trio, J. Brahms’ Horn Trio with Yakov Shapiro (horn), and Gabriel Fauré’s C minor Quartet with Rudolf Barshai (viola).

Leonid Kogan was the first Soviet violinist to play and record Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto (“To the Memory of an Angel”). He also made a famous recording of Khachaturian’s Violin Concerto on RCA (his American debut recording), a version still considered the most exciting reading of the work.

Sources

- Violin Concerto (Beethoven) on Wikipedia

- “Beethoven – Violin Concerto in D” on the Classic FM website

- Beethoven’s Violin Concerto (1806) on Moris Senegor’s website

- Leonid Kogan on Wikipedia