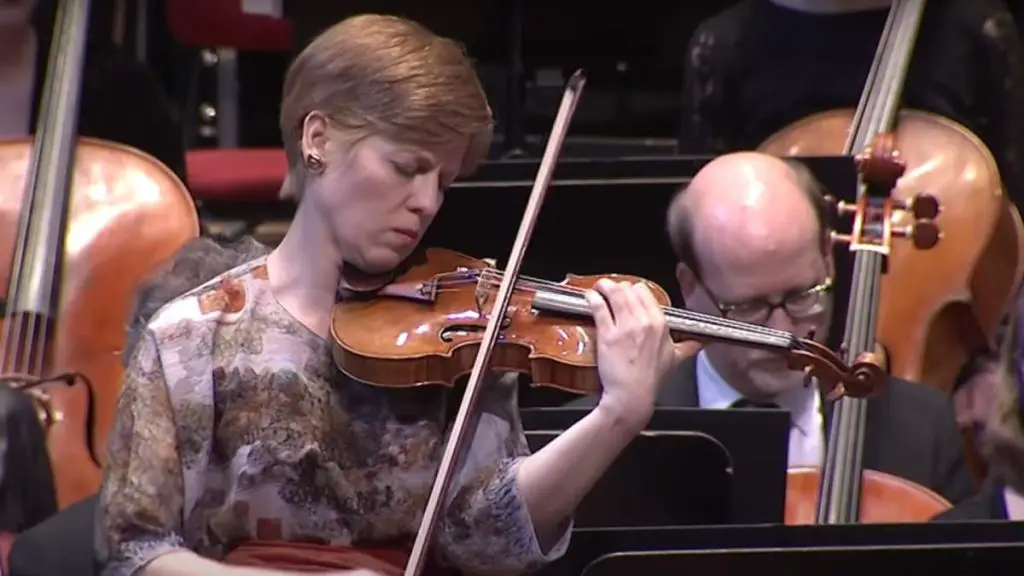

Accompanied by the Radio Filharmonisch Orkest (Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra), French virtuoso violinist René-Charles “Zino” Francescatti performs Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61. Conductor: Jean Fournet. This performance was recorded on May 13, 1973.

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, holds a special place in the violin repertoire as a work of profound depth and technical demands. Composed in 1806, the concerto marries the composer’s distinctive robustness and melodic richness with the graceful, refined qualities inherent in the violin. Its creation marked a significant point in Beethoven’s compositional life, a period that saw the deepening of his heroic style, which was to crystallize in the “Symphony No. 5” that followed.

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto was written for Franz Clement, a noted violinist of the day, who premiered the piece at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna. It’s interesting to note that the concerto did not immediately gain its now-celebrated status. The initial performance was reportedly under-rehearsed, and it didn’t help that Clement interrupted the concerto with a display of his own virtuosity, playing a piece of his own on one string with the violin upside down. The concerto, with its noble simplicity and lack of flashy virtuosity that was popular at the time, was somewhat overlooked, with critics and audiences unsure of what to make of it.

It wasn’t until 1844, nearly four decades after its composition, that the Beethoven Violin Concerto began to secure its place in the canon. This resurrection was thanks to the efforts of another virtuoso, Joseph Joachim, who was only 12 years old at the time. Joachim performed the concerto in London under the baton of Felix Mendelssohn, another towering figure in the musical landscape of the 19th century. The performance was a triumph, and the concerto began to receive the recognition it deserved.

What makes Beethoven’s Violin Concerto remarkable is its synthesis of virtuosity and lyrical beauty. It’s composed on a grand scale, with a broad, sweeping first movement that contrasts with the more intimate and ornate second movement, leading into a lively finale. The orchestration is notable for its use of timpani, which in the opening bars sets a rhythmic motif that is a key part of the concerto’s identity.

This work also signifies Beethoven’s exploration of the violin’s capabilities, moving away from the traditional showy concerto towards a more integrated relationship between the soloist and the orchestra. The soloist is often engaged in a dialogue with the ensemble, rather than standing apart as the star of the show. This approach was innovative at the time and contributed to the concerto’s initially lukewarm reception; it didn’t conform to the expectations of the genre during that era.

Despite its rocky beginnings, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is now revered as a cornerstone of violin literature, beloved by audiences and esteemed by violinists for its expressive depth and the technical challenges it poses. Its performance requires a soloist who not only has impeccable technique but also conveys the philosophical weight of Beethoven’s vision.

The concerto remains a testament to Beethoven’s ability to transform the potential of a musical form. It is a profound musical statement that encapsulates the dramatic journey of its own acceptance and the evolving tastes of the concert-going public.

Movements

1. Allegro ma non troppo

The first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, marked Allegro ma non troppo, unfolds on a grand scale, characterized by its expansive sonata form. It is notable for its majestic opening with four beats of the timpani, a motif that reappears and evolves throughout the movement, serving as a structural and thematic cornerstone.

Following this distinctive introduction by the timpani, the orchestra gently lays out the first theme, a broad, lyrical melody that establishes the contemplative and grand character of the movement. This theme is then developed and expanded, showcasing Beethoven’s mastery of orchestration and thematic development. The second theme of the movement provides a contrast, introducing a sense of lyrical tranquility.

When the solo violin enters, it does not with a flashy statement as was customary in many concertos of the time, but rather with a series of trills that echo the orchestral introduction, seamlessly blending with the established material. The violin then embarks on an exploration of the themes introduced by the orchestra, embellishing and expanding upon them with intricate passages and expressive variations.

The development section takes the listener through a journey of modulation and transformation, as Beethoven weaves the thematic material through different keys and orchestrations, building tension and complexity. This tension is then resolved in the recapitulation, where the main themes are revisited and restated by the orchestra and soloist, bringing back the initial grandeur and serenity.

Throughout the movement, Beethoven makes use of the solo violin’s expressive range, from the singing quality of its higher register to the robust and resonant tones of its lower strings. The cadenza, typically an improvised or written-out passage for the soloist, offers a showcase for technical brilliance and interpretative depth. While Beethoven did not originally write a cadenza for this concerto, several violinists and composers have provided their own; perhaps the most famous ones are those written by the 19th-century virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim and by Beethoven himself, albeit for the piano version of the concerto.

Clocking in at around 20-25 minutes, depending on the interpretation and the choice of cadenza, the first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is a testament to the composer’s vision of the concerto as a symphonic work with the violin as a first among equals-a soloist that both stands out and integrates within the tapestry of the full orchestra. The movement captures the essence of Beethoven’s middle period, where the heroic and the lyrical meet, creating music that is as emotionally rich as it is structurally sophisticated.

2. Larghetto

The second movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, marked Larghetto, offers a stark contrast to the first movement’s expansive dynamism. This movement unfolds as a series of variations on a tranquil, lyrical theme, providing a contemplative interlude between the energetic outer movements.

At the heart of the Larghetto is its theme, a serene and song-like melody introduced by the strings and woodwinds. The theme is simple and stately, with a tender quality that is characteristic of Beethoven’s lyrical writing. It’s this simplicity and the clear, singing line that give the movement its reflective quality.

When the violin enters, it picks up this melody and elaborates upon it with grace and elegance. The solo violin part is marked by delicate ornamentation and filigree, showcasing the instrument’s capacity for intimate expression rather than virtuosic display. Beethoven’s writing here emphasizes the warmth and expressive depth of the violin, utilizing long-breathed phrases and subtle variations in dynamics and articulation to create a rich emotional landscape.

The orchestration remains delicate throughout, providing a soft cushion of sound that allows the solo violin to shine. The movement is structured as a set of double variations, with the violin and orchestra taking turns in developing the theme. The variations are not merely decorative; they delve deeper into the emotional core of the theme, exploring different aspects of its character and mood.

Throughout the movement, there is a profound sense of dialogue – not just between the soloist and the orchestra, but between the movement’s own serene disposition and the more dramatic moments that emerge within the variations. These moments of heightened emotion never overpower the overall tranquility of the movement, instead adding depth and contrast to its peaceful narrative.

The Larghetto, with its gentle pace and reflective tone, serves as an essential emotional and structural bridge in the concerto. It provides a moment of repose and introspection, a space for the listener to absorb and reflect upon the complexities of the first movement before being launched into the vivacity of the finale.

Beethoven’s second movement is often described as an oasis of calm, and it exemplifies his ability to achieve profound expression through simplicity and restraint. In performance, the movement demands a soloist capable of great subtlety and expressiveness, able to sustain the listener’s attention with a tone that is at once pure and imbued with a deep sense of feeling. It’s a movement that, while less flashy than the outer movements, captures the essence of Beethoven’s musical poetry.

3. Rondo. Allegro

The finale of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto is marked Rondo: Allegro, is a spirited finale that brings the concerto to a triumphant close. This movement is characterized by its lively rondo form, where a principal theme (the “refrain”) alternates with contrasting episodes.

The rondo theme in this movement is a buoyant, rhythmic melody introduced by the solo violin that has a folk-like, danceable quality to it. This main theme is catchy and memorable, and its rhythmical vigor provides a joyful contrast to the introspective Larghetto that precedes it. The movement has an almost playful character, with the solo violin part demanding a combination of technical agility and musical wit.

Following the rondo principle, the main theme recurs several times throughout the movement, interspersed with contrasting sections that offer a variety of moods and colors. These episodes explore different textures and thematic material, allowing the soloist moments of lyrical expression as well as further opportunities for virtuosic display. Beethoven’s skill in orchestration ensures that these transitions are seamless and that the overall momentum of the movement is maintained.

One of the movement’s delights is the way Beethoven integrates the solo violin with the orchestral fabric. While the violin clearly dominates with the rondo theme and the most brilliant passages, there is a sense of partnership with the orchestra that harks back to the conversational dynamic established in the first movement. The orchestra is more than just an accompaniment; it is an active participant in the musical dialogue.

The cadenza, typically inserted before the final return of the rondo theme, is another moment for the soloist to shine. As with the first movement, Beethoven did not originally compose a cadenza for the violin here, and as such, violinists have often turned to cadenzas written by other composers or have composed their own. The cadenza is an opportunity for the violinist to demonstrate technical prowess while also encapsulating themes from the movement in a display of creative interpretation.

Beethoven concludes the movement with a coda that ramps up the excitement, often incorporating a faster tempo (Presto) and bringing back the rondo theme in a spirited and triumphant fashion. This coda ensures that the concerto ends on a high note, with energy and brilliance that leave the listener uplifted.

The third movement is a testament to Beethoven’s ability to blend virtuosic demands with melodic charm. It provides an exuberant ending to a concerto that spans a wide emotional range, from the bold statements of the first movement to the lyrical beauty of the second, culminating in the cheerful and vivacious finale.

Zino Francescatti

René-Charles “Zino” Francescatti (9 August 1902 – 17 September 1991) was a French virtuoso violinist. He was a notable figure in the world of classical music, celebrated for his exquisite violin performances and a career that spanned many decades, leaving a lasting impact on the musical landscape.

Born into a musical family in Marseilles, with both of his parents being violinists, Francescatti was immersed in a rich musical environment from the very beginning. His prodigious talent became apparent early on, as he took up the violin at the tender age of three. His quick recognition as a child prodigy was not mere happenstance; it was the result of his exceptional talent and the fertile musical ground from which he grew, nurtured by a lineage that included the tutelage of his father, a student of Camillo Sivori, who was the only pupil of the legendary Niccolò Paganini.

Francescatti’s ascent in the world of classical music was meteoric. By the age of ten, he had not only made his debut but did so with a performance of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, a piece that demands a deep understanding and a high level of technical prowess, hinting at his mastery even at such a young age.

Moving to Paris in 1927, Francescatti began to share his knowledge through teaching at the École Normale de Musique and conducting the Concerts Poulets. His influence, however, was not confined to France; a world tour in 1931 marked the beginning of his international prominence. His American debut in 1939, performing Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 1 with Sir John Barbirolli and the New York Philharmonic, set the stage for what would be a highly acclaimed international career.

His performances were not only technically superb but also deeply expressive, embodying the works of Mendelssohn, Saint-Saëns, Bruch, and others with a rare combination of precision and passion. His recordings, such as those of the Beethoven violin-piano sonatas with Robert Casadesus, have been praised for their artistry and continue to be a reference point for violinists worldwide.

The “Hart” Stradivarius of 1727, on which Francescatti performed, became part of his musical identity. The instrument is one of the many storied Stradivarius violins, known for their unparalleled craftsmanship and the exceptional tone quality they afford their players. That Francescatti was associated with such a remarkable instrument speaks volumes about his standing in the classical music community.

Upon retiring in 1976, Francescatti did not merely rest on his laurels; he established the Zino Francescatti Foundation, ensuring that his legacy would continue by supporting the development of young violinists. The establishment of an international violin competition in Aix-en-Provence in 1987 in his honor further signifies the esteem in which he was held and his enduring influence on the world of classical violin music.

Francescatti’s life and work are a testament to the combination of innate talent, rigorous training, and musical expression. His career not only showcases the possibilities of individual achievement but also serves as an inspiration for future generations of musicians. His recordings remain treasures of classical music, capturing the sound and spirit of a master whose contributions to the violin repertoire continue to resonate through concert halls around the world.

Sources

- Violin Concerto (Beethoven) on Wikipedia

- Zino Francescatti on Wikipedia

- Cecilia Bartoli sings Ombra Mai Fu [From Händel’s Serse] - October 10, 2024

- Chopin: Scherzo No. 3 [İlyun Bürkev] - September 14, 2024

- César Franck: Violin Sonata [Argerich, Capuçon] - September 8, 2024