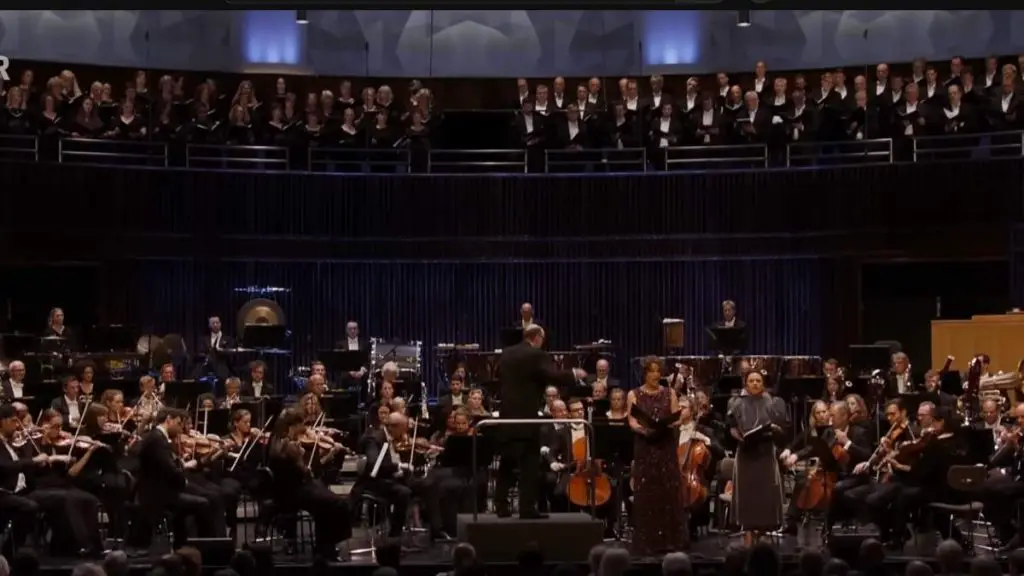

Conducted by Leonard Bernstein, the London Symphony Orchestra performs Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, known as the “Resurrection Symphony”. Edinburgh Festival Chorus with soloists – soprano: Sheila Armstrong, mezzo-soprano: Janet Baker. Recorded during the 1974 Edinburgh Festival.

Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection”

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, famously known as the “Resurrection” Symphony, is one of the most profound and ambitious works in the symphonic repertoire. Composed primarily in the 1890s, this symphony reflects Mahler’s deep philosophical and existential musings, particularly his thoughts on life, death, and resurrection. The work is monumental not just in its musical scope but also in its emotional and spiritual breadth.

The “Resurrection” Symphony is distinguished by its large-scale structure, which is characteristic of Mahler’s approach to symphonic composition. Mahler sought to create more than just music; he aimed to encapsulate a whole range of human experiences and emotions, making each of his symphonies a world unto itself. This symphony, in particular, is known for its exploration of themes of despair, redemption, and the afterlife, deeply influenced by Mahler’s own life experiences and philosophical inquiries.

Mahler’s approach to this symphony was innovative and groundbreaking. He expanded the traditional symphonic form, not just in length but also in the use of vocal elements. The inclusion of a choir and soloists in the later parts of the symphony was a significant departure from the norm, adding a new dimension to the work. This integration of vocal and orchestral elements allows Mahler to express his complex ideas more fully, blending poetry and music to create a powerful narrative arc.

The “Resurrection” Symphony also reflects Mahler’s mastery of orchestration. His use of the orchestra is remarkable for its detail and complexity, showcasing his ability to create a wide range of textures and colors. This aspect of the symphony contributes significantly to its emotional impact, as Mahler uses the orchestra not just to create music but to evoke profound emotional responses.

Thematically, the symphony delves into the ideas of mortality and the possibility of life after death. Mahler’s own spiritual journey and his reflections on the meaning of life and death are central to the narrative of the symphony. These themes resonate throughout the work, giving it a philosophical depth that is rare in the symphonic genre.

In performance, the “Resurrection” Symphony is a formidable challenge for any orchestra and conductor due to its length, complexity, and the emotional depth required. It demands not only technical proficiency but also a deep understanding of Mahler’s unique musical language and his philosophical worldview.

Movements

1. Allegro maestoso

The first movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” is a powerful and emotionally charged piece that sets the tone for the entire symphony. Known as “Allegro maestoso,” this movement is notable for its dramatic intensity and complex structure.

This movement begins with a slow introduction that immediately establishes a solemn and dramatic mood. The introduction features a funeral march, which is a key element that Mahler uses to introduce the themes of death and mourning that are central to the symphony. The funeral march theme is derived from Mahler’s own “Totenfeier” (Funeral Rites), a stand-alone piece he composed earlier, which he later integrated into this symphony.

After the introduction, the movement transitions into a faster, more agitated section. This part is characterized by a vigorous and turbulent orchestral texture, reflecting a sense of inner turmoil and existential struggle. The music here is often intense and dramatic, with frequent changes in dynamics and tempo, showcasing Mahler’s mastery of orchestral writing and his ability to convey deep emotions through music.

Throughout the movement, Mahler makes use of a large orchestra, employing a wide range of instruments to create a rich tapestry of sounds. This orchestration allows him to explore a variety of textures and colors, adding depth and complexity to the music. The use of leitmotifs, or recurring musical themes, is also evident in this movement. These motifs not only help to unify the movement but also serve as musical symbols for the various themes and ideas that Mahler is exploring.

One of the most striking features of this movement is its dramatic contrasts. Mahler juxtaposes moments of intense, almost overwhelming, power with passages of quiet introspection. This contrast creates a sense of emotional depth and complexity, drawing the listener into the psychological and spiritual journey that is at the heart of the symphony.

The movement ends with a powerful and climactic passage, which then subsides into a more subdued and reflective conclusion. This ending leaves the listener with a sense of unresolved tension, setting the stage for the subsequent movements of the symphony.

2. Andante moderato

The second movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” offers a stark contrast to the intense and dramatic first movement. Titled “Andante moderato,” this movement is more lyrical and reflective, providing a sense of calm and contemplation.

Characterized by its graceful and almost dance-like quality, the second movement has a distinctly different mood from the rest of the symphony. Mahler indicated that this movement should convey the feeling of a serene and uncomplicated world, a reminiscence of the past. It evokes a sense of nostalgic reflection, perhaps looking back on the joys and simplicities of life.

The structure of this movement is more straightforward compared to the complex, sprawling nature of the other movements. It’s largely built around a Ländler, a traditional Austrian and Bavarian dance that was a precursor to the waltz. This choice of form is significant, as it reflects Mahler’s fondness for incorporating elements of Austrian folk music into his compositions, a nod to his cultural roots.

Throughout the movement, the orchestration is lighter and more delicate than in the first movement. Mahler uses the orchestra to create a gentle, flowing melody that is both soothing and poignant. The strings often carry the main thematic material, with woodwinds and horns providing rich, warm colors that add to the movement’s pastoral and tranquil character.

One of the most notable aspects of this movement is its use of tempo and rhythm. The dance-like rhythm is a key element, providing a sense of graceful motion and flow. Mahler plays with the tempo subtly, using slight accelerations and decelerations to add expressiveness to the music, evoking a sense of nostalgia and longing.

Despite its seemingly simple and serene exterior, there’s an underlying complexity to the movement. It’s not just a straightforward dance but also a reflection of deeper emotions and memories. This duality is a hallmark of Mahler’s style, where seemingly simple musical ideas often contain a wealth of emotional depth and meaning.

3. In ruhig fließender Bewegung (With quietly flowing movement)

The third movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” is a unique and pivotal part of the symphony, marked by its complexity and profound symbolism. Titled “In ruhig fließender Bewegung” (With quietly flowing movement), this movement reflects Mahler’s innovative approach to symphonic composition and his deep exploration of existential themes.

This movement is based on Mahler’s setting of “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” (Saint Anthony of Padua’s Sermon to the Fishes), a part of “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” (The Youth’s Magic Horn), a collection of German folk poems that Mahler frequently turned to for inspiration. The text of the poem describes Saint Anthony preaching to the fish, who listen to him, but then return to their usual ways as soon as he leaves. This serves as a metaphor for the futility of his words and the indifference of the world, a theme that resonates with the existential questions Mahler explores throughout the symphony.

Musically, the third movement is a scherzo, but it’s far from the light-hearted character typically associated with such pieces. Instead, it has a mocking, ironic quality. The music is filled with contrasts and unexpected turns, reflecting the underlying sense of disillusionment and existential irony in the text. The orchestration is intricate, with Mahler using the full range of the orchestra to create a tapestry of sound that is both complex and vivid.

The movement opens with a series of irregular rhythms and dissonances, creating a sense of instability and restlessness. This introduction sets the tone for a movement characterized by sudden changes in mood and texture. The music shifts between moments of sarcasm, melancholy, and fleeting moments of tranquility, painting a vivid picture of the poem’s narrative and its deeper philosophical implications.

One of the defining features of this movement is its rhythmic complexity. Mahler employs a variety of rhythms and tempos, often juxtaposing them in a way that adds to the sense of disorientation and unease. This rhythmic diversity, combined with the frequent shifts in orchestration and dynamics, makes the third movement both challenging and engaging.

The movement’s conclusion brings a return to the opening themes, but with a sense of having journeyed through a diverse emotional landscape. This return provides a sense of closure, but it is a closure tinged with irony and introspection, in line with the overall mood of the movement.

4. “Urlicht” (Primal light)

The fourth movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” marks a significant shift in both tone and texture from the preceding movements. This movement, often referred to as “Urlicht” (Primeval Light), is relatively brief, but it plays a crucial role in the symphony’s narrative and emotional journey.

“Urlicht” is a song for alto solo, derived from Mahler’s earlier collection of songs based on the “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” texts. The text of “Urlicht” is imbued with profound spiritual and existential themes. It speaks of a longing for release from earthly suffering and a desire to transcend to a higher, more heavenly existence. This longing for redemption and transformation is central to the overall theme of resurrection that permeates the symphony.

Musically, the fourth movement stands in stark contrast to the complex and tumultuous third movement. It is characterized by its simplicity and starkness, with a focus on the vocal line. The orchestration is restrained, creating an intimate and contemplative atmosphere. This sparseness allows the voice to take center stage, conveying the deep emotion and spiritual longing of the text.

The melody of “Urlicht” is deeply expressive, with a folk-like quality that resonates with the text’s simplicity and profundity. The alto soloist’s role is to convey a sense of innocence and earnestness, embodying the human yearning for spiritual release and redemption.

The orchestration, while minimal compared to other movements, is profoundly effective. Mahler uses the orchestra to create a gentle, supportive backdrop for the vocal line, with the instrumental textures adding depth and resonance to the words. The use of lower strings and brass lends a warmth and richness to the music, creating a sense of groundedness and solemnity.

“Urlicht” serves as a pivotal moment in the symphony, providing a moment of introspection and calm before the grandeur and complexity of the final movement. It acts as a bridge, both thematically and emotionally, leading the listener from the existential questioning of the earlier movements to the resolution and transcendence of the finale.

In essence, the fourth movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 is a profound meditation on the themes of suffering, redemption, and the human longing for something beyond the earthly realm. Its simplicity and emotional depth make it one of the most poignant moments in the symphony, showcasing Mahler’s ability to convey profound existential themes through both text and music.

5. Im Tempo des Scherzos (In the tempo of the scherzo)

The finale of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” is a monumental conclusion to this epic symphony. This movement is not only the longest but also the most complex and dramatic part of the symphony, bringing together the themes and motifs introduced in the previous movements into a powerful and transcendent climax.

Mahler’s fifth movement begins with a sudden and dramatic outburst, a marked contrast to the intimate and reflective nature of the fourth movement. This opening sets the stage for a movement that is characterized by its dramatic shifts in mood, texture, and orchestration. The music oscillates between moments of intense turmoil and serene beauty, reflecting the symphony’s overarching themes of death, resurrection, and eternal life.

One of the most striking features of this movement is its use of chorus and soloists. After the initial orchestral outburst, the music gradually builds towards the entrance of the chorus, which adds a new dimension to the symphony. The chorus, often singing softly at first, eventually rises to a powerful climax, adding to the sense of drama and intensity. The text sung by the chorus and soloists is based on the “Resurrection Ode” by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, with additional lines by Mahler himself. This text reinforces the themes of resurrection and redemption that are central to the symphony.

The orchestration in this movement is vast and complex, with Mahler employing a wide range of instruments and sonic effects to create a rich tapestry of sound. The use of off-stage instruments, such as trumpets and horns, adds to the sense of spatial and sonic expansiveness. Mahler’s skillful orchestration creates a series of climactic moments, each building on the last, leading to the final, overwhelming climax.

Throughout the movement, Mahler interweaves various musical themes from the earlier movements, creating a sense of unity and cohesiveness within the symphony. These thematic recurrences serve to tie together the work’s diverse movements and reinforce the underlying narrative of death and resurrection.

The movement, and the symphony as a whole, concludes with a grand choral finale, where the chorus and orchestra join forces to deliver a triumphant and uplifting message of hope and renewal. This finale is one of the most celebrated passages in all of Mahler’s works, renowned for its emotional power and its profound sense of catharsis.

Shelia Armstrong

Dr. Sheila Armstrong (born Ashington, 13 August 1942) is an English soprano, equally noted for opera, oratorio, symphonic music, and lieder.

Educated at the Royal Academy of Music, she was co-winner of the Kathleen Ferrier Award in 1965, and as of 2011 was a trustee of the award fund.

She was active in English opera and oratorio from 1965, making her Covent Garden debut in 1983, and appeared in concerts and recitals, again mainly in England. She also made many recordings, notably of English music.

Armstrong retired in 1993, at the age of 51.

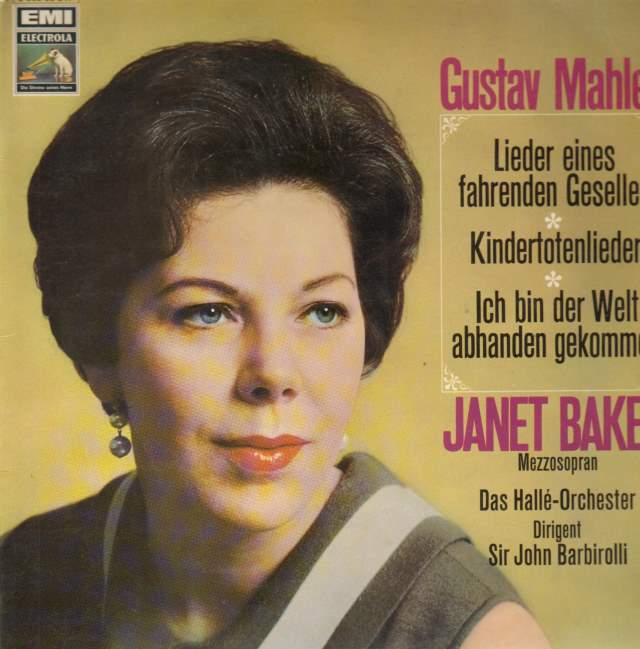

Janet Baker

Dame Janet Abbott Baker, CH, DBE, FRSA (born 21 August 1933) is an English mezzo-soprano best known as an opera, concert, and lieder singer.

She was particularly closely associated with baroque and early Italian opera and the works of Benjamin Britten. During her career, which spanned the 1950s to the 1980s, she was considered an outstanding singing actress and widely admired for her dramatic intensity, perhaps best represented in her famous portrayal as Dido, the tragic heroine of Berlioz’s magnum opus, Les Troyens.

As a concert performer, Dame Janet was noted for her interpretations of the music of Gustav Mahler and Edward Elgar. David Gutman, writing in Gramophone, described her performance of Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder as “intimate, almost self-communing.”

Janet Baker was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1970 and appointed to Dame Commander (DBE) in 1976. She was appointed a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in 1993. In 1968, she was initiated as an Honorary Member of Sigma Alpha Iota International Music Fraternity by the Alpha Omicron Chapter at Occidental College, California, United States.

She received the Léonie Sonning Music Prize of Denmark in 1979. She is the recipient of both Honorary Membership (1987) and the Gold Medal (1990) of the Royal Philharmonic Society. In 2008, she received the Distinguished Musician Award from the Incorporated Society of Musicians and in 2011 she was installed as an Honorary Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Musicians at a ceremony in the City of London.

She was voted into Gramophone magazine’s inaugural Hall of Fame in 2012.

Sources

- Symphony No. 2 (Mahler) on Wikipedia

- Sheila Armstrong on Wikipedia

- Janet Baker on Wikipedia