In a series marking the 250th year of his birth, we analyse the brilliance of Ludwig van Beethoven.

Around 1806, Beethoven sought advice on violin fingering from the Italian violinist Felix Radicati in connection with the three great string quartets of his middle period, the so-called “Razumovsky” Quartets, Opus 59.

Radicati impertinently asked whether Beethoven really considered these pieces to be music, to which he airily replied, “Oh, they are not for you, but for a later age!”

And Beethoven was right. His music was for a later age in ways he could scarcely have imagined.

Peter McCallum, University of Sydney

Enduring resonance

He would not have anticipated, for example, that English cricket captain Mike Brearley would whistle the opening cello theme of the first of those very quartets, when walking on to face Australian fast bowlers in 1981.

Or that, as on 1 October 1959, just before the artistic suffocation of the Cultural Revolution, Mao Tse Tung and Nikita Krushchev would listen to the heroic strains of his Egmont Overture to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, a celebration capped off later that month with a joint East German/Chinese performance of his Ninth Symphony in the newly completed Great Hall of the People in Tiananmen Square.

In the 250 years since his birth, Beethoven’s music has served myth-making agendas both personal and political, cultural and commercial, noble and nefarious.

He has been depicted in countless artworks, in popular culture, and provided inspiration for fictional characters in works from Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, and Romain Roland’s Jean Christophe to Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange.

As French poet and novellist Victor Hugo said, this is music where “the dreamer will recognise his dream, the sailor his storm, Elijah his whirlwind […] and the wolf his forests”.

Powerful and personal

Beyond the mythologising, hagiography and exploitation, the music itself retains a potent power to move listeners in deeply personal ways.

In E. M. Forster’s 1910 novel Howard’s End, Helen listens to the moment in his Fifth Symphony when Beethoven interrupts the exultant finale with a malignant return of the sardonic Scherzo theme – usually a light and jovial musical form. Helen hears in it a confirmation that “the splendour of life might boil over and waste to steam and froth”. That, she concludes, is why you can trust Beethoven when he says other things.

Why do listeners, like Helen, continue to find truth in the music’s stirring energy and transcendence?

Although there are as many answers as there are listeners, it is possible to point to some enduring virtues in his music and work habits that offer a glimpse into the mystery of the artistic process.

Beethoven had a capacity to put forward a memorable, well-shaped, malleable, often open-ended idea that announces itself as a kind of proposition. This can be heard famously in the first four notes of his Fifth Symphony.

One doesn’t need musical education or experience to hear how Beethoven builds from those insistent four notes the ensuing tumultuous clamour and stormy intensity.

The same applies to a comparable four-note knocking motive that grabs the listener’s ear just after the opening idea in the Piano Sonata in F minor, the “Appassionata“.

Lenin claimed to know this sonata inside out, and, though other music frequently got on his nerves, said he could listen to it every day.

Propelled by rhythm

The memorability of Beethoven’s ideas owes much to their rhythmic definition, energy and elasticity. At times his rhythm is impulsive and disruptive as though refusing to adhere to well-behaved phrases and the constraints of convention.

His Third Symphony, the “Eroica”, begins with the simplest of bold affirmative ideas – two emphatic chords.

Yet scarcely has the ensuing theme begun but it is distracted, and Beethoven has to start it twice more before it gains its full stride.

Later in the same movement the opening chords almost grind the music to a halt. Beethoven uses rhythm not just to propel the music but to articulate large-scale form and struggle.

In other works, particularly in his late period (1816 to his death in 1827), he used rhythm to change our experience of time itself, as in the Arietta of his final Piano Sonata, the Sonata in C minor, Opus 111.

A sublimely simple theme is progressively subdivided to reach a peak of jaunty activity anticipating the syncopated rhythms of 20th century jazz, only to break completely to a moment of radical trance-like stasis.

As Milan Kundera points out in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, it is as though Beethoven is pointing to 17th century philosopher Blaise Pascal’s two infinities – the infinitely large and the infinitely small.

Early in his career, Beethoven found ways of using harmony to give the impression of leaving the expected path to survey a new unexplored vista. He often used this device just before the close (in the Piano Sonata Opus 7, for example).

Listen to the solo violin entry in the central development section (around the 11:02 mark) of the Violin Concerto in D where the soloist returns after a long orchestral tutti, initially repeating the idea she opened with before unexpectedly shifting outwards to an expressive theme in the highest sweet notes of the violin.

More than words

In his book Beethoven Hero Scott Burnham points out this is music that seems to be telling us something though what it is telling us is, as Mendelssohn put it, too exact for words.

It trivialises the music to say, as one of Beethoven’s earliest critics A. B. Marx did, that the opening of the Eroica Symphony depicts Napoleon mounting his steed on the battlefield.

Beethoven had a way of using these resources to convey a narrative of urgent thought, whether intimate or epic.

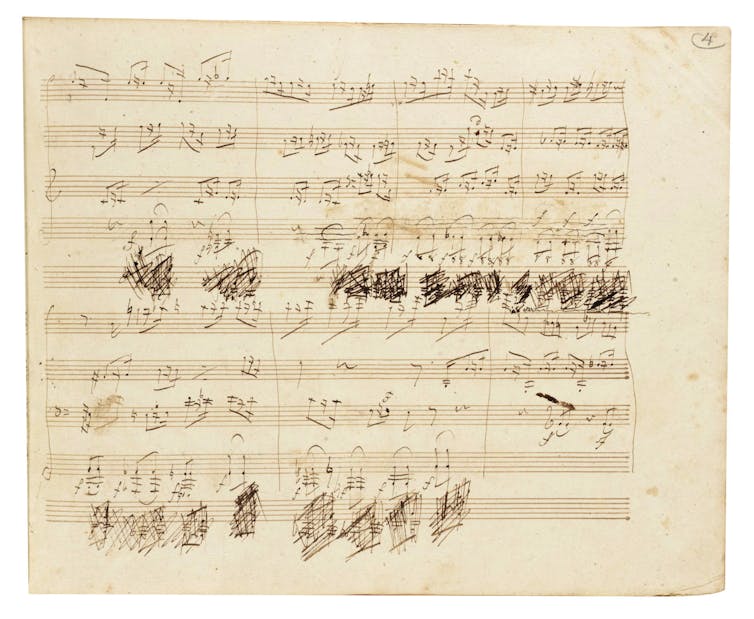

Beethoven did not arrive at these moments of numinous truth easily. From at least 1798 when he was 28 years old until his death in 1827, he wrote his ideas in sketchbooks, some large for home use (over 30 of these survive in full or in part) and a slightly greater number of handmade books that he carried in his pocket. The magisterial flow of the Eroica Symphony, mentioned above, was worked out over as many as 12 continuity drafts.

Towards the end of his life the process became more intense. Between the completion of the Ninth Symphony in February 1824 and his death in 1827, Beethoven filled at least 1,899 pages of sketches for his five late string quartets and other projects, not counting a further 700 pages of completed scores and copies. This represents over 2,500 densely-packed, often almost illegible pages in less than three years.

Even leaving aside the creative effort involved, two substantial periods of illness in 1825 and 1826/7 and time out for rows with publishers and his nephew Carl (the latter almost ending in tragedy with the nephew’s unsuccessful suicide attempt in 1826), it represents substantial physical work.

Amid his own stormy life, he averaged two and a half pages a day, every single day for 32 months – hieroglyphic postcards for a later age.

Peter McCallum, Registrar and Academic Director (Education), University of Sydney

Read the original article.