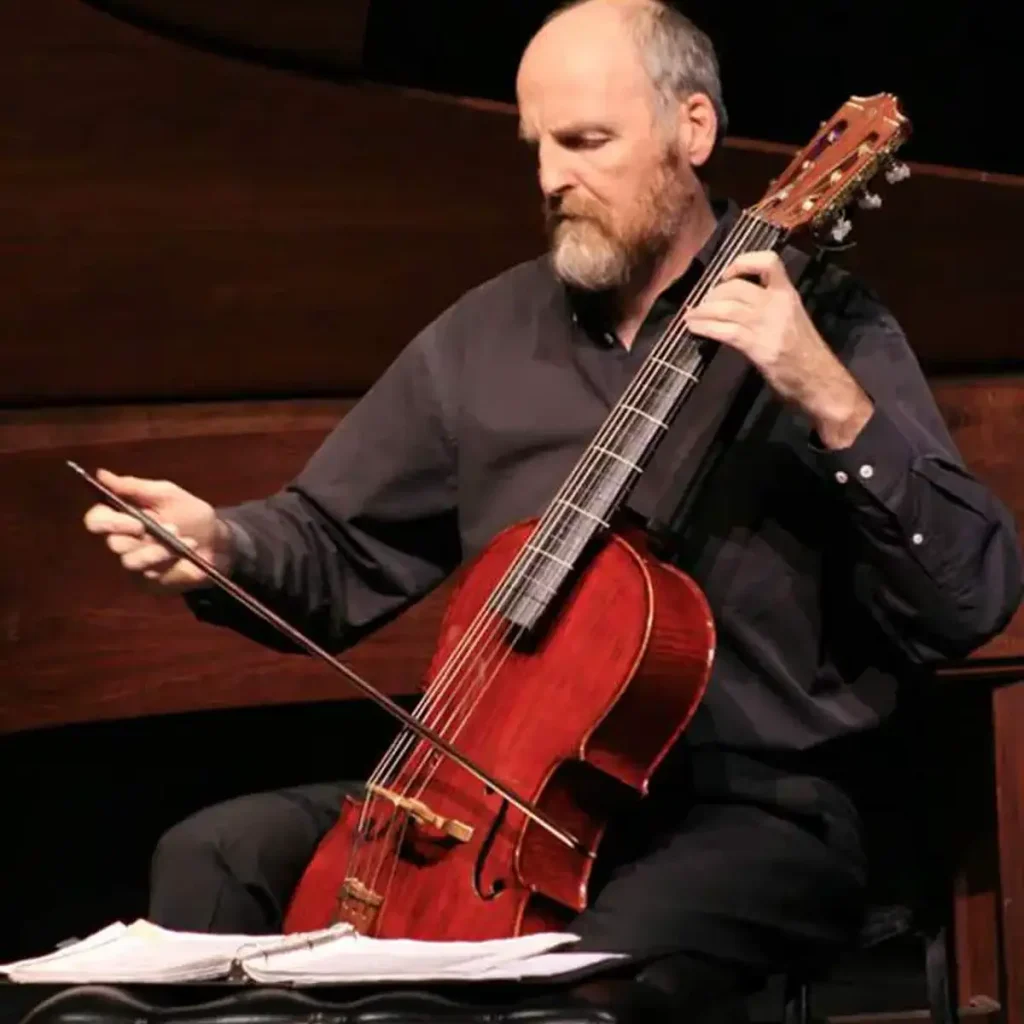

Hungarian cellist Miklós Perényi and Hungarian-born virtuoso British classical pianist and conductor András Schiff perform Franz Schubert’s Sonata in A minor for Arpeggione and Piano, D. 821, also known as the “Arpeggione Sonata”. The sonata is originally written for arpeggione, a six-stringed musical instrument, fretted and tuned like a guitar, but bowed like a cello, and thus similar to the bass viola da gamba.

Franz Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata

Franz Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata, formally known as Sonata in A minor for Arpeggione and Piano, D. 821, is a unique and remarkable piece in the classical music repertoire. Composed in 1824, this work is notable for its original instrumentation, having been written for the arpeggione, an uncommon instrument. The arpeggione, also referred to as the “guitar violoncello,” was a hybrid between the guitar and cello, invented in the early 19th century. However, its popularity was short-lived, and it soon fell into obscurity.

This piece is the only notable piece extant for arpeggione, which was invented in 1823 by the Viennese guitar maker Johann Georg Stauffer (January 26, 1778 – 24 January 1853). Today, the piece is heard almost exclusively in transcriptions for cello and piano or viola and piano.

Despite the decline of the arpeggione, Schubert’s sonata gained a new lease of life through adaptations for more familiar instruments. Today, it is most commonly performed on the cello or viola, accompanied by the piano. This adaptability testifies to the sonata’s musical versatility and the enduring appeal of its melodies and harmonies.

The sonata itself is a work of profound emotion and lyricism, characteristics that are hallmarks of Schubert’s style. It reflects the composer’s mastery in blending melodic simplicity with complex harmonic structures, creating music that is both accessible and deeply moving. The work is imbued with a sense of introspection and melancholy, a feature typical of Schubert’s late compositions.

In terms of its structure, while we’re not delving into the specifics of the movements, it’s significant to note that the sonata follows the traditional classical form. This approach showcases Schubert’s ability to work within classical frameworks while infusing them with his unique musical language.

The Arpeggione Sonata, though originally composed for an instrument that no longer holds a place in standard orchestral ensembles, has become a beloved piece in the classical music repertoire. Its performance on modern instruments has allowed it to transcend its historical origins, highlighting Schubert’s enduring legacy as a composer who could evoke deep emotions through his music.

The sonata is not only a testament to Schubert’s compositional skill but also a reflection of the musical innovations of his time. Its enduring popularity in the classical music world is a tribute to its beauty and the universal appeal of its melodies.

Movements

1. Allegro moderato

The first movement of Franz Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata, marked as Allegro moderato, is a captivating and lyrical piece that beautifully showcases Schubert’s compositional style. This movement, like the rest of the sonata, was originally composed for the arpeggione, an instrument that combined features of the guitar and cello, but today it is most often performed on the cello or viola, accompanied by piano.

The Allegro moderato begins with a gentle, expressive melody that immediately establishes the emotional tone of the piece. This theme, introduced by the piano and then taken up by the arpeggione (or cello/viola in modern performances), is characterized by its lyrical quality and Schubert’s signature use of melodic simplicity combined with rich harmonic underpinnings. The opening melody is both tender and introspective, setting the stage for a movement that is deeply expressive and nuanced.

As the movement progresses, Schubert weaves a dialogue between the piano and the arpeggione, with each instrument echoing and complementing the other. This interplay highlights the sonata form, with its exposition, development, and recapitulation, yet Schubert’s treatment of the form is filled with inventive touches and emotional depth.

One of the remarkable aspects of this movement is Schubert’s use of modulation. The journey through different keys adds a sense of drama and contrast to the piece, moving through moments of brightness and darkness, which is a hallmark of Romantic music. Despite these modulations, the movement maintains a sense of cohesion, with the recurring main theme serving as an anchor.

The development section of the movement is particularly noteworthy for its complexity and emotional intensity. Here, Schubert explores new harmonic territories, building tension and creating a sense of longing or yearning. This section demonstrates Schubert’s skill in developing thematic material in a way that is both intellectually satisfying and emotionally resonant.

As the movement draws to a close, the recapitulation brings back the main theme, offering a sense of resolution and closure. However, Schubert’s treatment of the recapitulation is nuanced, with subtle variations and shifts in dynamics that add depth to the return of the theme.

2. Adagio

The second movement of Franz Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata is marked “Adagio” and stands as a profound testament to Schubert’s lyrical and expressive capabilities. This movement, originally composed for the arpeggione and piano, is now most commonly performed on cello or viola, accompanied by piano, given the historical obsolescence of the arpeggione.

Characterized by its slow tempo and deeply reflective nature, the Adagio opens with a delicate and introspective piano introduction. This sets a somber and contemplative mood, preparing the listener for the entry of the arpeggione (or cello/viola). When the string instrument enters, it does so with a melody that is at once simple and profoundly moving. The melody, typical of Schubert’s style, is both singable and deeply emotive, showcasing his unparalleled ability to craft melodies of great beauty and expressiveness.

The interaction between the piano and the string instrument in this movement is particularly noteworthy. The piano provides a harmonious and often understated accompaniment that supports and enhances the melody of the string instrument. This partnership creates a dialogue that is both intimate and expressive, with each instrument contributing to the overall mood of introspective melancholy.

One of the key features of this movement is its use of dynamics and phrasing to convey emotion. Schubert’s careful control of musical tension and release, through the use of crescendos and diminuendos, adds depth and nuance to the performance. The phrasing, with its subtle rubatos and expressive articulations, brings the melody to life, making it breathe and speak to the listener.

The harmonic language of the Adagio is also notable. Schubert employs rich and sometimes unexpected harmonies that add complexity and depth to the music. These harmonies enhance the emotional impact of the piece, creating moments of tension and resolution that resonate with the listener.

As the movement progresses, it maintains its reflective and somber character, but there are moments where the music rises in intensity, adding a sense of yearning or longing. These moments are brief, however, and the movement generally retains its subdued and contemplative nature.

The Adagio concludes with a return to the tranquility of the opening, gradually fading away in a manner that leaves the listener in a state of reflective calm. This ending is typical of Schubert’s ability to conclude a movement in a way that feels both satisfying and introspective, leaving a lasting emotional impact.

The second movement of the Arpeggione Sonata is a masterpiece of lyrical expression, demonstrating Schubert’s extraordinary ability to convey deep emotions through music. It is a movement that speaks to the heart, showcasing the beauty and depth of his musical language.

3. Allegretto

The third and final movement of Franz Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata is a vivacious and rhythmic piece, marked as “Allegretto.” This movement contrasts sharply with the introspective and lyrical nature of the preceding Adagio, showcasing a different aspect of Schubert’s compositional range. Originally written for the arpeggione and piano, like the rest of the sonata, it is now most commonly played on the cello or viola along with the piano, due to the arpeggione’s historical obsolescence.

The Allegretto opens with a light and lively melody that immediately sets a playful and energetic tone. This theme, introduced by the piano and then echoed by the string instrument, is characterized by its rhythmic vitality and dance-like quality. The melody has a buoyant, almost folk-like character, reflecting Schubert’s ability to infuse his compositions with a sense of immediacy and charm.

As the movement progresses, Schubert develops this initial theme through a series of variations. These variations showcase not only the technical capabilities of the instruments but also the composer’s skill in thematic development. The variations range from lively and spirited to more lyrical and subdued, offering a rich tapestry of moods and textures.

One of the striking features of this movement is its rhythmic drive. Schubert employs a variety of rhythmic patterns to maintain the movement’s momentum, creating a sense of forward motion that is both engaging and invigorating. The interplay between the piano and the string instrument further enhances this rhythmic energy, with each instrument adding its own dynamic accents and flourishes.

Harmonically, the Allegretto is playful and adventurous, with Schubert exploring a range of keys and modulations. These harmonic shifts add an element of surprise and delight to the movement, keeping the listener engaged and entertained. Despite these shifts, the movement maintains a sense of coherence and unity, tied together by the recurring main theme.

The concluding section of the Allegretto brings the movement to a spirited and joyful close. Schubert skillfully brings back the main theme, now more triumphant and exuberant, leading to a lively and satisfying conclusion. This ending encapsulates the movement’s overall character, one of energy, joy, and the sheer pleasure of music-making.

Miklós Perényi

Miklós Perényi (born 5 January 1948) is a Hungarian cellist. He was born in Budapest into a musical family and studied at the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest with Ede Banda and Enrico Mainardi. He continued his studies at the Accademia Santa Cecilia, graduating in 1962. In 1963 he won a prize at the Pablo Casals International Violoncello Competition in Budapest.

In 1965 and 1966 he studied with Pablo Casals in Zermatt and Puerto Rico and afterward performed at Marlboro Festival for four consecutive years. In 1974 he became a lecturer and in 1980 a professor at the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Music, but while teaching continued to perform internationally. He has been a regular guest of the Theatre de la Ville in Paris for solo works and chamber music performances.

András Schiff

Sir András Schiff is a Hungarian-born British classical pianist and conductor. Schiff is world renowned for his interpretations of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann. He won the 1990 Grammy Award for “Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra)” for English Suites by Bach. Schiff was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in her 2014 Birthday Honours for services to music.

The awards that Schiff has won include:

- a 1990 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra) – English Suites by Bach

- a 1990 Gramophone Award for a Schubert recital with Peter Schreier

- the Bartók Prize in 1991

- the Claudio Arrau Memorial Medal in 1994

- the Kossuth Prize in 1996

- the Léonie Sonning Music Prize in 1997

- honorary membership in the Beethoven House in Bonn, awarded in 2006 for his complete recording of Beethoven’s piano sonatas

- the Italian prize, Premio della Critica Musicale Franco Abbiati, also for his Beethoven cycle in 2007

- also in 2007, the Royal Academy of Music Bach Prize, sponsored by the Kohn Foundation, was awarded to “an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to the performance and/or scholarly study of Johann Sebastian Bach”

- the Wigmore Hall Medal in 2008

- also in 2008, the Klavier-Festival Ruhr Prize, for outstanding pianistic achievement

- the Robert Schumann Prize of the City of Zwickau in 2011

- and in January 2012, the Golden Mozart Medal of the International Stiftung Mozarteum.

He has been made an Honorary Professor by music academies in Budapest, Detmold, and Munich and is a Special Supernumerary Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford University. He is a Fellow of the Royal Northern College of Music. In December 2013, the Royal Philharmonic Society awarded him its Gold Medal.

He has created a Knight Bachelor in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list of 2014, for services to music.

Sources

- Arpeggione Sonata on Wikipedia

- Arpeggione on Wikipedia

- Miklós Perényi on Wikipedia

- András Schiff on Wikipedia

![Schubert: Arpeggione sonata [Argerich, Maisky]](https://cdn-0.andantemoderato.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Martha-Argerich-Mischa-Maisky-Schubert-Sonata-D-821-Arpeggione-1024x576.jpg)